The Advantages of Using Appreciated Securities to Fund a Donor-Advised Fund

Many people fund their donor-advised funds with cash, but gifting appreciated securities can be a smarter move. By donating stocks, mutual funds, or ETFs instead of cash, you can avoid capital gains tax and still claim a charitable deduction for the asset’s full market value. Our analysis at Greenbush Financial Group explains how this strategy can create a double tax benefit and help you give more efficiently.

By Michael Ruger, CFP®

Partner and Chief Investment Officer at Greenbush Financial Group

Many individuals fund their donor-advised funds (DAFs) with cash — but they may be missing out on a major tax-saving opportunity. By gifting appreciated securities (such as stocks, mutual funds, or ETFs) from a brokerage account instead of cash, taxpayers can avoid capital gains taxes and still receive a charitable deduction for the fair market value of the gift.

In this article, we’ll cover:

Why donor-advised funds have grown in popularity

The pros and cons of funding a DAF with cash

How gifting appreciated securities can create a double tax benefit

Charitable deduction limitations to keep in mind when using this strategy

The Rise in Popularity of Donor-Advised Funds

Donor-advised funds have become one of the most popular charitable giving vehicles in recent years. Much of this growth is tied to changes in the tax code — particularly the increase in the standard deduction.

Since charitable contributions are itemized deductions, taxpayers must itemize in order to claim them. But with the standard deduction now so high, fewer taxpayers itemize their deductions at all.

For example:

In 2025, the standard deduction for a married couple is $31,500.

Let’s say that a couple pays $10,000 in property taxes and donates $10,000 to charity.

Their total itemized deductions would be $20,000, which is still below the $31,500 standard deduction — meaning they’d receive no additional tax benefit for their $10,000 charitable gift.

That’s where donor-advised funds come in.

If this same couple plans to give $10,000 per year to charity for the next five years (totaling $50,000), they could “bunch” those future gifts into one year by contributing $50,000 to a donor-advised fund today. This larger, one-time contribution would push their itemized deductions well above the standard deduction threshold, allowing them to capture a significant tax benefit in the current year.

Another advantage is flexibility — the funds in a donor-advised account can be invested and distributed to charities over many years. It’s a way to pre-fund future giving while taking advantage of a larger immediate tax deduction.

Funding with Cash

It’s perfectly fine to fund a donor-advised fund with cash, especially if your goal is simply to capture a large charitable deduction in a single tax year.

Cash contributions are straightforward and qualify for a deduction of up to 60% of your adjusted gross income (AGI). But while this approach helps you maximize deductions, there may be an even more tax-efficient way to give — especially if you own highly appreciated investments in a taxable brokerage or trust account.

Using Appreciated Securities to Make Donor-Advised Fund Contributions

A potentially superior strategy is to contribute appreciated securities instead of cash. Doing so provides a double tax benefit:

Avoid paying capital gains tax on the unrealized appreciation of the asset.

Receive a charitable deduction for the fair market value of the donated securities.

Here’s an example:

Suppose you bought Google stock for $5,000, and it’s now worth $50,000.

If you sell the stock and then donate the $50,000 cash to your donor-advised fund, you’d owe capital gains tax on the $45,000 gain.

Alternatively, if you donate the stock directly to your donor-advised fund, you:

Avoid paying tax on that $45,000 unrealized gain, and

Still receive a $50,000 charitable deduction for the fair market value of the stock.

After the transfer, if you’d still like to own Google stock, you can repurchase it within your brokerage account — effectively resetting your cost basis to the current market value. This approach can help manage future capital gains exposure while supporting your charitable goals.

Charitable Deduction Limitations: Cash vs. Appreciated Securities

Whether you donate cash or appreciated securities, it’s important to understand the IRS limits on charitable deductions relative to your income. These limitations are based on a percentage of your adjusted gross income (AGI) and vary depending on the type of asset you donate:

This means if you donate appreciated securities worth more than 30% of your AGI, the excess amount can’t be deducted in the current year — but it can be carried forward for up to five additional years until fully utilized.

Being mindful of these limits ensures that your charitable giving strategy is both tax-efficient and compliant.

Final Thoughts

Using appreciated securities to fund a donor-advised fund can be one of the most effective ways to maximize your charitable impact and minimize taxes. By avoiding capital gains tax on appreciated assets and receiving a deduction for their full fair market value, you can create a powerful, ongoing giving strategy that benefits both your finances and your favorite causes.

Before implementing this strategy, it’s wise to work with your financial advisor or CPA to confirm eligibility, ensure proper documentation, and coordinate timing for optimal tax efficiency.

About Michael……...

Hi, I’m Michael Ruger. I’m the managing partner of Greenbush Financial Group and the creator of the nationally recognized Money Smart Board blog . I created the blog because there are a lot of events in life that require important financial decisions. The goal is to help our readers avoid big financial missteps, discover financial solutions that they were not aware of, and to optimize their financial future.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Why is donating appreciated securities to a donor-advised fund more tax-efficient than giving cash?

Donating appreciated securities allows you to avoid paying capital gains tax on the investment’s appreciation while still receiving a charitable deduction for its fair market value.

How does a donor-advised fund help maximize charitable deductions?

A donor-advised fund (DAF) allows you to “bunch” multiple years of charitable contributions into a single tax year, pushing your itemized deductions above the standard deduction threshold. This strategy can help you capture a larger tax benefit in the current year while retaining flexibility to distribute funds to charities over time.

What are the IRS deduction limits for donating appreciated securities versus cash?

Cash donations to public charities or donor-advised funds are generally deductible up to 60% of your adjusted gross income (AGI), while donations of appreciated securities are limited to 30% of AGI. Any unused deductions can typically be carried forward for up to five years.

Can I repurchase the same securities after donating them to a donor-advised fund?

Yes. After donating appreciated securities, you can repurchase the same investment within your brokerage account. This effectively resets your cost basis to the current market value, helping manage future capital gains exposure while maintaining your investment position.

Who might benefit most from using appreciated securities to fund a donor-advised fund?

This strategy is especially beneficial for investors with highly appreciated assets in taxable accounts who want to support charitable causes while reducing taxes. It can also help high-income earners manage taxable income in peak earning years.

What are some common mistakes to avoid when donating appreciated securities?

Common pitfalls include selling the securities before donating them (which triggers capital gains tax) or failing to meet IRS substantiation requirements for non-cash gifts. Working with a financial advisor or CPA ensures proper execution and documentation.

Does Changing Your State of Domicile Allow You To Avoid Paying Capital Gains Tax?

As individuals approach retirement, they often ask the tax question, “If I were to move to a state that has no state income tax in retirement, would it allow me to avoid having to pay capital gains tax on the sale of my investments or a rental property?” The answer depends on a few variables.

As individuals approach retirement, they will often ask the tax question, “If I were to move to a state that has no state income tax in retirement, would it allow me to avoid having to pay capital gains tax on the sale of my investments or a rental property?”. The answer depends on the following variables:

What type of asset did you sell?

When did you sell it?

What are the requirements to change domicile to another state?

Selling A Rental Property

We will start off by looking at the Rental Property sale scenario. If someone owns an investment property in New York and they plan to move to Florida the following year, would it be better to wait to sell the property until after they have officially changed their domicile to Florida to potentially avoid having to pay state income tax on the gain to New York? Or would they have to pay tax to New York either way?

Unfortunately, it is the latter of the two. If you own real estate in a state that has income tax and your property has gone up in value, you’ll have to pay tax on the gain to that state when you sell it—regardless of where you live. When someone pays tax to a state other than their state of domicile, they normally receive a credit for the tax paid to offset any tax owed to their state of domicile and avoid double taxation. But that raises the obvious question: What if the state of domicile has no income tax? What happens to the credit? Answer: it’s lost. In the example of someone domiciled in Florida—a state with no income tax—who sells a property in New York, which does have a state income tax, they would owe tax to New York on the gain. However, because Florida has no income tax, there would be nothing to offset, and the credit for taxes paid to New York is effectively lost.

Selling A Primary Residence

While selling a primary residence follows the real estate rules that we just covered, the one main difference is that there is a large gain exclusion when someone sells their primary residence, that does not apply to investment properties. The gain exclusion amounts are as follows:

Single Filer: $250,000

Married Filing Joint: $500,000

Based on these exclusion amounts, someone filing a joint tax return would have to realize a gain greater than $500,000 before they would owe any tax to the federal or state government when they sell their primary residence. Remember, it’s the gain, not the sales price. If someone purchased a house for $300,000 and sells it for $700,000, there is a $400,000 gain in the property. If they file a joint tax return, the full $400,000 is sheltered from taxation by the primary residence exclusion.

Once the gain exceeds $250,000 for a single filer or $500,000 for a joint filer, then the owner of the house would have to pay tax to the state the house is located in, regardless of their state of domicile at the time of the sale.

Selling Stocks or Investments

If someone has a large unrealized gain in their taxable brokerage account and they are considering moving to a state that has no income tax, they will ask, “If I wait to sell my stock until after I have officially changed my state of domicile, will I avoid having to pay state income tax on the realized gain?” The answer here is “Yes”. This is one of the advantages that investment holdings like stocks, bonds, ETFs, and mutual funds have over real estate investments.

For example, Jen lives in New York and purchased shares of Nvidia a few years back for $10,000, which are now worth $200,000. If she sold the shares now, she would have to pay a flat 15% long-term capital gain at the federal level, and approximately 6% ($11,400) to New York State. However, if Jen plans to move to Florida and waits to sell the Nvidia stock until after she has officially domiciled in Florida, she would still have to pay the 15% long-term capital gains tax to the Feds, but she would completely avoid having to pay tax on the gain to New York State, saving her $11,400 in taxes.

The Timing of The Sale of Stock is Key

When someone changes their state of domicile mid-year, which is most, a line in the sand is drawn from a tax standpoint. For example, if Jen moved from New York to Florida on May 15th, all investment activity between January 1st – May 14th would be taxed in New York, and all investment activity May 15th – December 31st would be taxed (essentially not taxed) in Florida. It’s for this reason that individuals who have taxable investment accounts and are planning to move to a more tax-favorable state within the next few years may be influenced as to when they decide to sell certain investments at a gain within their taxable investment portfolio.

IRA Distribution Taxation

Traditional IRA distributions are taxed at ordinary income tax rates, but the same timing principle applies; any distribution processed prior to the change in domicile would be taxed in their current state, and distributions processed after the change of domicile are taxed or, in some cases, not taxed, in their new state. If Roth conversions in retirement are part of your tax strategy, this is also one of the reasons why individuals will wait until they have become domiciled in the new state before actually processing Roth conversions.

What Are The Requirements To Change Your State of Domicile

The rules for changing your state of domicile are more complex than most people think. It’s not just “I have to be in that state for more than 6 months out of the year.” That may be one of the requirements, but there are many others. So many that we had to write a whole separate article on this topic, which can be found here:

Article: How To Change Your Residency To Another State for Tax Purposes

About Michael……...

Hi, I’m Michael Ruger. I’m the managing partner of Greenbush Financial Group and the creator of the nationally recognized Money Smart Board blog . I created the blog because there are a lot of events in life that require important financial decisions. The goal is to help our readers avoid big financial missteps, discover financial solutions that they were not aware of, and to optimize their financial future.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

Can moving to a state with no income tax help me avoid paying capital gains tax?

It depends on your income picture and the type of assets that you own. If you live in a state now that has income tax but you pay very little state income tax, moving to a state that has no income tax will have a minimal impact. However, if you specific sources of income, such as investment income or taxable income from Roth conversions, moving from a state that has income tax to a state with no income tax can have a meaningful impact.

Do I still owe state tax on the sale of a rental property after moving?

Yes. If you sell a rental property located in a state that imposes income tax, you must pay tax to that state on the gain, regardless of where you live at the time of sale. You receive a credit on the state tax paid to apply against any state tax due in your current state, but if there is no state income tax in your current state of domicile, the credit goes unused.

How is the sale of a primary residence taxed when moving to another state?

You can exclude up to $250,000 in gains if single or $500,000 if married filing jointly when selling your primary residence, provided you meet ownership and use requirements. Any gain above these thresholds is taxable to the state where the property is located, even if you’ve moved to a no-tax state.

Can I avoid state taxes on stock sales by moving before I sell?

Yes. If you wait to sell appreciated investments such as stocks, ETFs, or mutual funds until after establishing domicile in a no-income-tax state, you can avoid state tax on the capital gains. The timing of your move and the sale determines which state has taxing authority.

How does the timing of domicile change affect investment taxation?

When you change residency mid-year, income earned before the move is taxed by your former state, while income earned after is taxed under the new state’s rules. For example, investment gains realized before moving from New York to Florida would be taxed in New York, but gains realized afterward would not be.

Are IRA withdrawals and Roth conversions affected by state residency changes?

Yes. Distributions from traditional IRAs or Roth conversions made before changing residency are taxed in your former state, while those made afterward follow the tax rules of your new domicile. This timing can be strategically used to reduce state income taxes in retirement.

What are the main requirements to change your state of domicile for tax purposes?

Changing domicile involves more than just spending six months in another state. You must establish clear intent and presence — such as changing your driver’s license, voter registration, mailing address, and location of key assets — to prove your new primary residence for tax purposes.

Company Stock In Your 401(k)? Don’t Forget To Elect NUA

If you’re retiring or leaving your job and have company stock in your 401(k), understanding NUA (Net Unrealized Appreciation) could save you thousands in taxes. Many miss this valuable opportunity by rolling everything into an IRA without considering the tax implications. Our latest article breaks down how NUA works, common tax mistakes, and when choosing NUA makes sense. Learn how factors like your age, retirement timeline, and stock performance play a role. Don’t overlook this strategy if your company stock has grown significantly in value—it could make a big difference in your retirement savings.

For employees with company stock as an investment holding within their 401(k) accounts, there is a special distribution rule available that provides significant tax benefits called “NUA”, which stands for Net Unrealized Appreciation. The NUA option becomes available to employees who have either retired or terminated their employment with a company and are in the process of rolling over their 401(k) balances to an IRA. The purpose of this article is to help employees understand:

How does the NUA 401(k) distribution option work?

What are the tax benefits of electing NUA?

The immediate tax event that is triggered with an NUA election

What situations should NUA be elected?

What situations should NUA be AVOIDED?

Special estate tax rules for NUA shares

The Common Rollover Mistake

For employees who have company stock in their 401(k) and do not receive proper guidance, they can easily miss the window to make the NUA election, which can cost them thousands of dollars in additional taxes in their retirement years. When employees leave a company, it’s common for the employee to open a Rollover IRA and process a direct rollover of their entire balance in their 401(k) to their IRA to avoid triggering an immediate tax event as they move their retirement savings away from their former employer.

Example: Tim retires from Company ABC and has a $500,000 balance in that 401(k) plan; $200,000 of the $500,000 is invested in ABC company stock. He sets up a traditional IRA, calls the 401(k) provider, and requests that they process a direct rollover of the full $500,000 balance from his 401K to his IRA. The 401(k) platform processes the rollover, and Tim deposits the $500,000 to his IRA with no taxes being triggered. Then, Tim begins taking distributions from his IRA to supplement his income in retirement. On the surface, everything seems perfectly fine with this scenario. However, Tim may have completely missed a huge tax-saving opportunity by failing to request NUA treatment of his company stock within his 401(k) account.

How Does NUA Work?

When an employee has company stock in their 401(k) account and they go to take a distribution/rollover from their 401(k) after they leave employment with the company, they may be able to elect NUA treatment of the portion of their 401(k) that is invested in company stock. But what does NUA treatment mean? When an employee processes a rollover from their pre-tax 401(k) balance to their Rollover IRA, and then takes distributions from their IRA in the future, they have to pay ordinary income tax on all distributions taken from the IRA account. However, prior to requesting a full rollover of their 401(k) balance to their IRA, an employee with company stock in their 401(k) account can make an NUA election, which allows the appreciation in the stock within the 401(k) account to be taxed at long-term capital gains rates in the future as opposed to ordinary income tax rates which may be higher.

But employees must be aware that by electing NUA, it triggers an immediate tax event for the employee.

Here is how NUA works as an example. Sue has a 401(k) account with Company XYZ. The total balance of Sue’s 401(k) is $800,000, but $400,000 of the $800,000 balance is invested in XYZ company stock that Sue has accumulated over the past 20 years with the company. The cost basis of Sue’s $400,000 in company stock within the 401(k) is $50,000, so over that 20-year period, the company stock has gained $350,000 in value.

When Sue retires, instead of rolling over the full $800,000 balance to her Rollover IRA, she makes an NUA election. The NUA election will send the $400,000 in company stock within her 401(k) account to an after-tax brokerage account in Sue’s name as opposed to a Rollover IRA account. When that happens, Sue has to pay ordinary income tax, not on the full $400,000 value of the stock, but on the $50,000 cost basis amount of the company stock. The $350,000 in “unrealized gain” in the company stock is now sitting in Sue’s brokerage account, and when she sells the stock, she receives long-term capital gain treatment of the $350,000 gain, as opposed to paying ordinary income tax on the $350,000 gain if it was rolled over to her IRA.

But what happens to the rest of Sue’s 401(k) balance that was not invested in company stock? The non-company stock portion of Sue’s 401(k) account can be rolled over to a Rollover IRA and it’s a 100% tax-free event. She just pays ordinary income tax on future distributions from the IRA account.

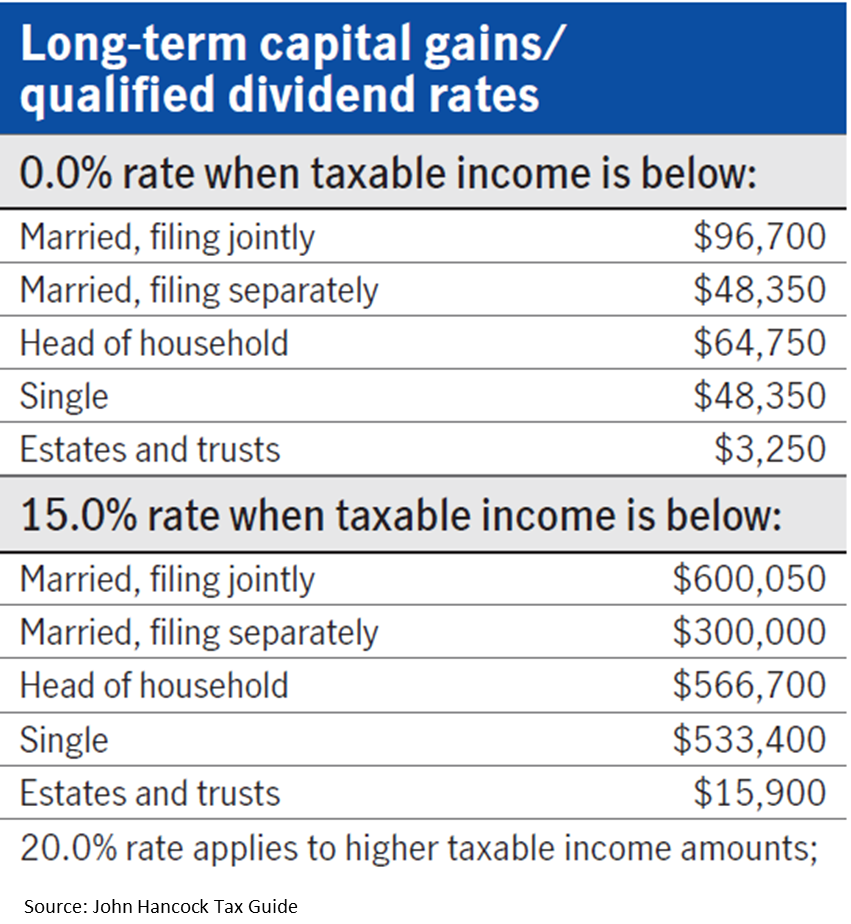

NUA – Long-Term Capital Gains Rates

Depending on Sue’s income level in retirement, her federal long-term capital gains rate may be 0%, 15%, or 20%, which may be lower than if she had realized the IRA distribution at ordinary income tax rates. Here is a quick chart that illustrates the 2025 long-term capital gains rates by filing status and income level:

NUA Triggers A Tax Event

Now let’s go back and review the tax event that was triggered when Sue requested the $400,000 transfer of her company stock from the 401(k) to her brokerage account. Again, when the NUA is processed, she only has to pay ordinary income tax on the cost basis amount of the stock, so in Sue’s case, in the year the NUA distribution takes place, she would have to report an additional $50,000 in taxable income. The tax liability generated could either be paid with her personal cash reserve or she could liquidate some of the company stock in her after-tax brokerage account to pay the taxes.

Timing of the NUA Distribution

There is a tax strategy associated with the timing of requesting the NUA distribution. If someone works for a company until September and then retires, they already have 9 months' worth of income in that tax year. In this case, it may be beneficial to process the rollover from the 401(k) with the NUA to the brokerage account the following tax year, when the individual’s W-2 income is completely off the table, so the taxable cost basis associated with the NUA election is potentially taxed at a lower rate since there is no W2 income the following year.

The Employee’s Age Matters for NUA

Because the cost basis of the company stock is treated like a cash distribution, if an employee takes an NUA distribution before age 55 and has already left the company, the cost basis would be subject to ordinary income tax and the 10% early withdrawal penalty.

NUA – Age 55 Exception To The 10% Early Withdrawal Penalty

Why age 55 and not 59½? Qualified retirement plans (401(k), 403(b), 457(b) plans) have a special exception to the under age 59½ 10% early withdrawal penalty. If you terminate employment with the company AFTER reaching age 55 and you take a cash distribution or NUA directly from the 401(k) plan, the employee is no longer subject to the 10% early withdrawal penalty. But an employee who terminates employment at age 54 and requests the NUA distribution at age 55 would still get hit with the 10% penalty because they did not separate from service AFTER reaching age 55.

The cost basis associated with the NUA distribution is treated the same as a regular cash distribution from a 401(k) plan.

When Electing NUA Makes Sense

There are certain situations where making the NUA election makes sense, and there are situations where it should be avoided. We will start off by reviewing the common situations where electing NUA makes sense in lieu of rolling over the entire balance to an IRA.

Large Unrealized Gain In The Company Stock

In order for the NUA election to make sense, there typically has to be a large unrealized gain built up in the company stock within the 401(k) plan. Said another way, the company stock has to have performed well within the 401(k) account. If the value of the company stock in an employee's 401(k) account is $200,000 and the cost basis is $170,000, if that employee elects an NUA and then transfers the $200,000 in stock to their brokerage account, it’s going to trigger a $170,000 immediate tax event and only $30,000 would receive long-term capital gains treatment. In this case, it’s probably not worth the tax hit.

In the example with Sue, she only had to pay ordinary income tax on $50,000 of the $400,000 in company stock, so the NUA would make more sense in her situation because she is shifting $350,000 to long-term capital gains treatment.

Ordinary Income Tax vs Long Term Capital Gains Rates

For NUA to make sense, it’s a race between what tax rate someone would pay if the money were distributed from a Rollover IRA and distributed at ordinary income tax rates versus the long-term capital gains tax rate if NUA is elected. Under current tax law, the federal tax rate jumps from 12% to 22% at $96,950 for a joint tax filer. On the surface it would seem that someone with under $96,950 in income might be better off rolling over the balance to an IRA and paying ordinary income tax rates at 12% instead of the long-term capital gains rate of 15%. However, if you look at the long-term capital gains tax rates in the table earlier in the article, if in 2025 a joint filer has income below $96,700, the long-term capital gains rate is 0%, and a 0% tax rate always wins.

Time Horizon Matters

An employee's time horizon to retirement also factors into the NUA decision. If an employee leaves a company at age 40, not only would they have to pay taxes and the 10% penalty on the cost basis of the NUA distribution, but by moving the company stock to a taxable brokerage account, they are losing the tax deferred accumulation benefit associated with the Rollover IRA for the next 19+ years. Since the brokerage account is a taxable account, the owner of the account has to pay taxes every year on dividends, interest, and realized gains produced by the brokerage account. If the company stock is liquidated and the full 401(k) balance is rolled over to an IRA, all of the investment income avoids immediate taxation and continues to accumulate within the IRA account. For taxpayers in higher tax brackets, this may have its advantages.

There are a lot of factors in the NUA decision, but in general, the shorter the timeline to when distributions will begin from retirement savings, the more it favors NUA; the longer the time horizon to retirement, the less it favors NUA over the benefits of continued tax deferred accumulation in a Rollover IRA account.

Reduce Future RMDs

For individuals who have a majority of their assets in pre-tax retirement accounts, like 401(k) and IRA accounts, and are fortunate enough to not need to take large distributions from those accounts in retirement because they have other sources of income, eventually when those individuals reach RMD age (73 or 75), the IRS is going to force them to start taking large taxable distributions out of their pre-tax retirement accounts.

For an individual in this situation, electing NUA can be an attractive option. Instead of their full 401(k) balance ending up in a Rollover IRA with a future RMD requirement, the company stock is sent to a brokerage account that does not require RMDs.

Estate Planning – No Step-Up In Cost Basis for NUA

Here is a little-known estate planning fact about NUA elections. Normally, when you have unrealized gains in a brokerage account and the owner of the account passes away, the beneficiaries of the estate receive a step-up in cost basis, which eliminates the taxable gain if the beneficiaries were to sell the stock. For individuals that elect NUA from a 401(k) account, there is a special rule that states if shares are deposited into a brokerage account as a result of an NUA election, the remaining portion of the NUA will be considered “income with respect of the decedent”, meaning the beneficiaries of the estate will have to pay long-term capital gains when they eventually sell those shares.

I’m not sure how this is tracked because when you move shares into a brokerage account that has NUA, if the shares continue to appreciate in value, and shares are bought and sold throughout the decedent’s lifetime, how do you determine which portion of the remaining unrealized gain was from the NUA election and which portion represents unrealized gains post NUA? A wonderful question for your tax professional if you end up in this situation.

When To Avoid NUA

As part of the analysis above, I highlighted a number of situations where an NUA election might not make sense, but a quick hit list is:

Company stock has not performed well in 401(k) account – high cost basis

High tax rate assessed on the cost basis amount during the year of NUA election

Employee under age 55 or 59½, potentially triggering early withdrawal penalty

Long time horizon to retirement (loss of tax deferred accumulation)

Ordinary tax rate lower or similar to long-term capital gains rate

About Michael……...

Hi, I’m Michael Ruger. I’m the managing partner of Greenbush Financial Group and the creator of the nationally recognized Money Smart Board blog . I created the blog because there are a lot of events in life that require important financial decisions. The goal is to help our readers avoid big financial missteps, discover financial solutions that they were not aware of, and to optimize their financial future.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

What is NUA and how does it work?

NUA, or Net Unrealized Appreciation, is a special tax rule that allows employees with company stock in their 401(k) to move that stock to a taxable brokerage account after leaving the company. The original cost basis of the stock is taxed as ordinary income, but the stock’s appreciation is later taxed at more favorable long-term capital gains rates instead of ordinary income tax rates.

When can employees use the NUA option?

NUA treatment is available only after separating from an employer due to retirement, termination, or death. It must be elected before rolling over company stock from the 401(k) to an IRA — otherwise, the opportunity is lost permanently.

What are the tax benefits of electing NUA?

The main advantage is that the appreciation in company stock is taxed at long-term capital gains rates (0%, 15%, or 20%) instead of higher ordinary income tax rates. This can lead to significant tax savings when the stock is eventually sold.

What tax event occurs when NUA is elected?

When NUA is processed, the employee must pay ordinary income tax on the stock’s cost basis in the year of distribution. The appreciation amount is not taxed until the stock is sold and is then treated as a long-term capital gain.

When does electing NUA make sense?

NUA is most beneficial when the company stock has a low cost basis and substantial unrealized gains. It can also be a good choice for retirees looking to reduce future required minimum distributions (RMDs) since the company stock moved to a brokerage account is no longer subject to RMDs.

When should NUA be avoided?

NUA may not make sense if the company stock has a high cost basis, the taxpayer is under age 55 (potentially triggering the 10% early withdrawal penalty), or if the individual’s ordinary income tax rate is similar to or lower than the long-term capital gains rate. It may also be less beneficial for those with many years until retirement who would lose the advantage of continued tax-deferred growth.

Does company stock transferred through NUA receive a step-up in basis at death?

No. Company stock distributed under NUA rules does not receive a full step-up in cost basis when the owner passes away. The portion of the gain representing the original NUA remains taxable to heirs as long-term capital gains when the shares are sold.

What’s the biggest mistake employees make with company stock in a 401(k)?

Many employees roll their 401(k) balances directly into an IRA without evaluating whether NUA treatment applies. Once the rollover is complete, the NUA opportunity is lost forever — potentially costing thousands in unnecessary future taxes.

Do I Have To Pay Tax On A House That I Inherited?

The tax rules are different depending on the type of assets that you inherit. If you inherit a house, you may or may not have a tax liability when you go to sell it. This will largely depend on whose name was on the deed when the house was passed to you. There are also special exceptions that come into play if the house is owned by a trust, or if it was gifted

Do I Have To Pay Tax On A House That I Inherited?

The tax rules are different depending on the type of assets that you inherit. If you inherit a house, you may or may not have a tax liability when you go to sell it. This will largely depend on whose name was on the deed when the house was passed to you. There are also special exceptions that come into play if the house is owned by a trust, or if it was gifted with the kids prior to their parents passing away. On the bright side, with some advanced planning, heirs can often times avoid having to pay tax on real estate assets when they pass to them as an inheritance.

Step-up In Basis

Many assets that are included in the decedent’s estate receive what’s called a step-up in basis. As with any asset that is not held in a retirement account, you must be able to identify the “cost basis”, or in other words, what you originally paid for it. Then when you eventually sell that asset, you don’t pay tax on the cost basis, but you pay tax on the gain.

Example: You buy a rental property for $200,000 and 10 years later you sell that rental property for $300,000. When you sell it, $200,000 is returned to you tax free and you pay long-term capital gains tax on the $100,000 gain.

Inheritance Example: Now let’s look at how the step-up works. Your parents bought their house 30 years ago for $100,000 and the house is now worth $300,000. When your parents pass away and you inherit the house, the house receives a step-up in basis to the fair market value of the house as of the date of death. This means that when you inherit the house, your cost basis will be $300,000 and not the $100,000 that they paid for it. Therefore, if you sell the house the next day for $300,000, you receive that money 100% tax-free due to the step-up in basis.

Appreciation After Date of Death

Let’s build on the example above. There are additional tax considerations if you inherit a house and continue to hold it as an investment and then sell it at a later date. While you receive the step-up in basis as of the date of death, the appreciation that occurs on that asset between the date of death and when you sell it is going to be taxable to you.

Example: Your parents passed away June 2019 and at that time their house is worth $300,000. The house receives the step-up in basis to $300,000. However, lets say this time you rent the house or don’t sell it until September 2020. When you sell the house in September 2020 for $350,000, you will receive the $300,000 tax-free due to the step-up in basis, but you’ll have to pay capital gains tax on the $50,000 gain that occurred between date of death and when you sold house.

Caution: Gifting The House To The Kids

In an effort to protect the house from the risk of a long-term event, sometimes individuals will gift their house to their kids while they are still alive. Some see this as a way to remove themselves from the ownership of their house to start the five-year Medicaid look back period, however, there is a tax disaster waiting for you with the strategy.

When you gift an asset to someone, they inherit your cost basis in that asset, so when you pass away, that asset does not receive a step-up in basis because you don’t own it and it’s not part of your estate.

Example: Your parents change the deed on the house to you and your siblings while they’re still alive to protect assets from a possible nursing home event. They bought the house 30 years ago for $100,000, and when they pass away it’s worth $300,000. Since they gifted the assets to the kids while they were still alive, the house does not receive a step-up in basis when they pass away, and the cost basis on the house when the kids sell it is $100,000; in other words, the kids will have to pay tax on the $200,000 gain in the property. Based on the long-term capital gains rates and possible state income tax, when the children sell the house, they may have a tax bill of $44,000 or more which could have been completely avoided with better advanced planning.

How To Avoid Paying Capital Gains Tax On Inherited Property

There are ways to both protect the house from a long-term event and still receive the step-up in basis when the current owners pass away. This process involves setting up an irrevocable trust to own the house which then protects the house from a long-term event as long as it’s held in the trust for at least five years.

Now, we do have to get technical for a second. When an asset is owned by an irrevocable trust, it is technically removed from your estate. Most assets that are not included in your estate when you pass do not receive a step-up in basis; however, if the estate attorney that drafts the trust document puts the correct language within the trust, it allows you to protect the assets from a long-term event and receive a step-up in basis when the owners of the house pass away.

For this reason, it’s very important to work with an attorney that is experienced in handling trusts and estates, not a generalist. It only takes a few missing sentences from that document that can make the difference between getting that asset tax free or having a huge tax bill when you go to sell the house.

Establishing this trust can sometimes cost between $3,000 and $6,000. But by paying this amount upfront and doing the advance planning, you could save your heirs 10 times that amount by avoiding a big tax bill when they inherit the house.

Making The House Your Primary

In the case that the house is gifted to the children prior to the parents passing away and the house is not awarded the step-up in basis, there is an advance tax planning strategy if the conditions are right to avoid the big tax bill. If one of the children would be interested in making their parent’s house their primary residence for two years, then they are then eligible for either the $250,000 or $500,000 capital gains exclusion.

According to current tax law, if the house you live in has been your primary residence for two of the previous five years, when you go to sell the house you are allowed to exclude $250,000 worth of gain for single filers and $500,000 worth of gain for married filing joint. This advanced tax strategy is more easily executed when there is a single heir and can get a little more complex when there are multiple heirs.

About Michael……...

Hi, I’m Michael Ruger. I’m the managing partner of Greenbush Financial Group and the creator of the nationally recognized Money Smart Board blog . I created the blog because there are a lot of events in life that require important financial decisions. The goal is to help our readers avoid big financial missteps, discover financial solutions that they were not aware of, and to optimize their financial future.