What Is an ETF & Why Have They Surpassed Mutual Funds in Popularity?

There is a sea change happening in the investment industry where the inflows into ETF’s are rapidly outpacing the inflows into mutual funds. When comparing ETFs to mutual funds, ETFs sometimes offer more tax efficiency, trade flexibility, a wider array of investment strategies, and in certain cases lower trading costs and expense ratios which has led to their rise in popularity among investors. But there are also some risks associated with ETFs that not all investors are aware of……..

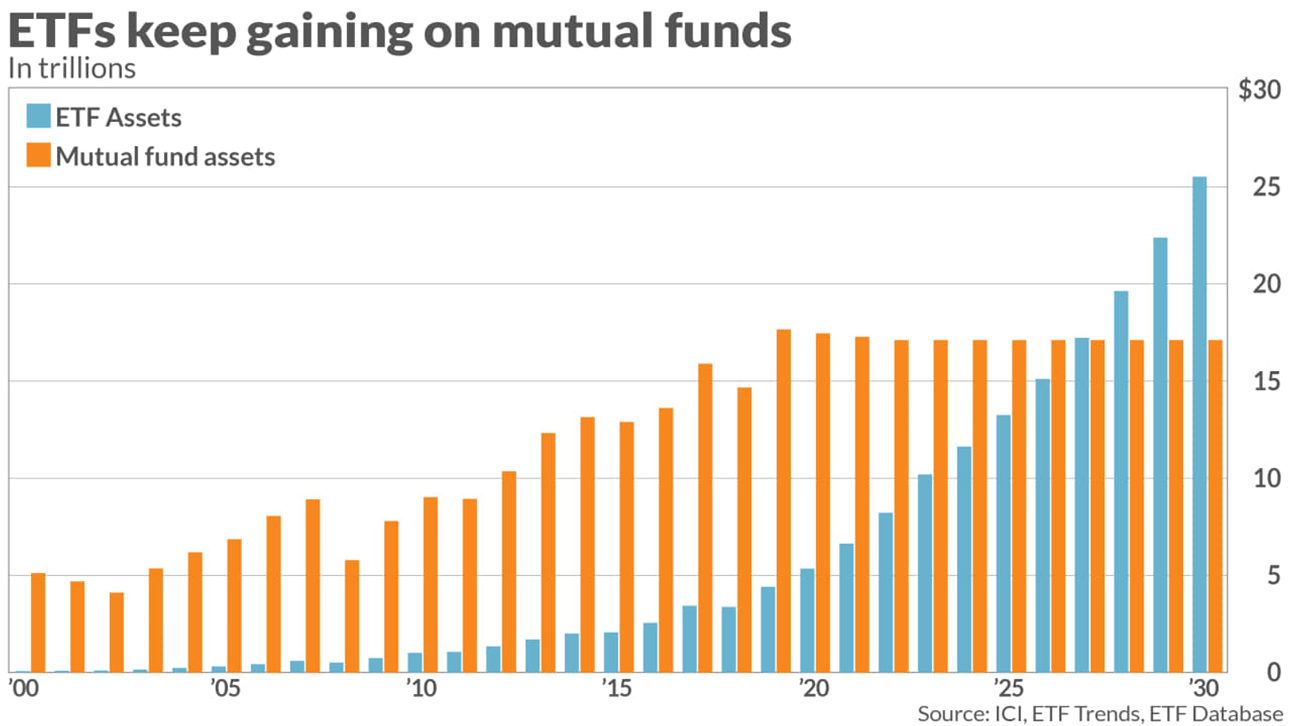

There is a sea change happening in the investment industry where the inflows into ETF’s are rapidly outpacing the inflows into mutual funds. See the chart below, showing the total asset investments in ETFs vs Mutual Funds going back to 2000, as well as the Investment Company Institute’s projected trends going out to 2030.

Why is this happening? While mutual funds and ETFs may look similar on the surface, there are several dramatic differences that are driving this new trend.

What is an ETF?

ETF stands for Exchange Traded Fund. On the surface, an ETF looks very similar to an index mutual fund. It’s a basket of securities often used to track an index or an investment theme. For example, Vanguard has the Vanguard S&P 500 Index EFT (Ticker: VOO), but they also have the Vanguard S&P 500 Index Fund (Ticker: VFIAX); both aim to track the performance of the S&P 500 Index, but there are a few differences.

ETFs Trade Intraday

Unlike a mutual fund that only trades at 4pm each day, an ETF can be traded like a stock intraday, so if you want to see $10,000 of the Vanguard S&P 500 ETF at 10am, you can do that, versus if you are invested in the Vanguard S&P 500 Index Fund, it will only trade at 4pm which may be at a better or worse price depending where the S&P 500 index finished the trading day compared to the price at 10am.

How ETFs Are Traded

When it comes to comparing ETFs to Mutual Funds, a big difference is not only WHEN they trade, but also HOW they trade. When you sell a mutual fund, your shares are sold back to the mutual fund company at 4pm and settled in cash. An exchange traded fund trades like a stock where shares are “exchanged” between a buyer and a seller in the open market, which is where ETF’s get their name from. They are “exchanged”, not redeemed like mutual fund shares.

ETF Tax Advantage Over Mutual Funds

One of the biggest advantages of ETFs over mutual funds is their tax efficiency, which relates back to what we just covered about how ETFs are traded. When you redeem mutual fund shares, if the fund company does not have enough in its cash reserve within the mutual fund itself, it has to go on the open market and sell securities to raise cash to meet the redemptions. Like any other type of investment account, if the security that they sell has an unrealized gain, selling the security to raise cash creates a taxable realized gain, and then the mutual fund distributes those gains to the existing shareholders, typically at the end of the calendar year as “capital gains distributions” which are then taxed to the current holders of the mutual funds.

If the current shareholders are holding that mutual fund in a taxable account when the capital gains distribution is issued, the shareholder needs to report that capital gains distribution as taxable income. This never seemed fair because that shareholder didn't redeem any shares, however since the mutual fund had to redeem securities to meet redemptions, the shareholders that remain unfortunately bear the tax burden.

Example: Jim and Sarah both own ABC Growth Fund in their brokerage accounts. ABC has performed well for the past few years, so Sarah decides to sell her shares. The mutual fund company then has to sell shares of stock within its portfolio to meet the redemption request, generating a taxable gain within the mutual fund portfolio. At the end of the year, ABC Growth Fund issues a capital gain distribution to Jim, which he must pay tax on, even though Jim did not sell his shares, Sarah did.

ETFs do not trigger capital gains distributions to shareholders because the shares are exchanged between a buyer and a seller, an ETF company does not have to redeem securities within its portfolio to meet redemptions. So, you could technically have an ABC Growth Mutual Fund and an ABC Growth ETF, same holdings, but the investor that owns the mutual fund could be getting hit with taxed on capital gains distribution each year while the holder of the ETF has no tax impact until they sell their shares.

Holding ETFs In A Taxable Account vs Retirement Account

Tax efficiency matters the most in taxable accounts, like brokerage accounts. If you are holding an ETF or mutual fund within an IRA or 401(k) account, since retirement accounts by nature are tax deferred, the capital gains distributions being issued by the mutual fund companies do not have an immediate tax impact on the shareholders because of the tax deferred nature of retirement accounts. For this reason, there has been less urgency to transition from mutual funds to ETFs in retirement accounts.

Many ETFs Don’t Trade In Fractional Shares

The second reason why ETFs have been slower to be adopted into employer sponsored retirement plans, like 401(k) plans, is most ETFs, like stocks, only trade in whole shares. Example: If you want to buy 1 share of Google, and Google is trading for $163 per share, you have to have $163 in cash to buy one whole share. You can’t buy $53 of Google because it’s not enough to purchase a whole share. Most ETF’s work the same way. They have a share price like a stock, and you have to purchase them in whole shares. Mutual funds by comparison trade in fractional shares, meaning while the “share price” or “NAV” of a mutual fund may be $80, you can buy $25.30 of that mutual fund because they can be bought and sold in fractional shares.

This is why from an operational standpoint, mutual funds can work better in 401(k) accounts because you have employees making all different levels of contributions each pay period to their 401(K) accounts - Jim is contributing $250 per pay period, Sharon $423 per pay period, Scott $30 per pay period. Since mutual funds can trade in fractional shares, the full amount of those contributions can be invested each pay period, whereas if it was a menu of ETFs that only traded in full shares, there would most likely be uninvested cash left over each pay period because only whole shares can be purchased.

ETF’s Do Not Have Minimum Initial Investments

Another advantage that ETF’s have over mutual funds is they do not have “minimum initial investments” like many mutual funds do. For example, if you look up the Vanguard S&P 500 Index Mutual Fund (Ticker VFIAX), there is a minimum initial investment of $3,000, meaning you must have at least $3,000 to buy a position in that mutual fund. Whereas the Vanguard S&P 500 Index ETF (Ticker: VOO) does not have a minimum initial investment, the current share price is $525.17, so you just need $525,17 to purchase 1 share.

NOTE: I’m not picking on Vanguard, they are in a lot of my example because we use Vanguard in our client portfolios, so we are very familiar with how their mutual funds and ETFs operate.

ETFs Do Not CLOSE To New Investors

Every now and then a mutual fund will declare either a “soft close” or “hard close”. A soft close means the mutual fund is closed to “new investors” meaning if you currently have a position in the mutual fund, you are allowed to continue to make deposits, but if you don’t already own the mutual fund, you can no longer buy it. A “hard close” is when both current and new investors are no longer allowed to purchase shares of the mutual fund, existing shareholders are only allowed to sell their holdings.

Mutual Funds will sometimes do this to protect performance or their investment strategy. If you are managing a Small Cap Value Mutual Fund and you receive buy orders for $100 billion, it may be difficult, if not impossible to buy enough of the publicly traded small cap stock to put that cash to work. Then, the fund manager might have to expand the stock holding to “B team” selections, or begin buying mid-cap stock which creates style drift out of the core small cap value strategy. To prevent this, the mutual fund will announce either a soft or hard close to prevent these big drifts from happening.

Arguably a good thing, but if you love the fund, and they tell you that you can’t put any more money into it, it can be a headache for current shareholders.

Since ETFs trade in the open market between buyers and sellers, they cannot implement hard or soft closes, it just becomes, ‘how much are the current holders of the ETF willing to sell their shares for in the open market to the buyers’.

ETFs Can Offer A Wider Selection of Investment Strategies

With ETFs, there are also a wider variety of investment strategies to choose from and the number of ETFs available in the open market are growing rapidly.

For example, if you want to replicate the performance of Brazil’s stock market within your portfolio, iShares has an ETF called MSCI Brazil (Ticker: EWZ) which seeks to track the investment results of an index composed of Brazilian equities. While traditional indexes exist within the ETF world like tracking the total bond market or S&P 500 Index, EFTs can provide access to more limited scope investment strategies.

ETF Liquidity Risk

But this brings me to one of the risks that shareholders need to be aware of when buying thinly traded ETFs. Since they are exchange traded funds, if you want to sell your position, you need a buyer that wants to buy your shares, otherwise there is no way to sell your position. One of the metrics we advise individuals to look at before buying an ETF is the daily trade volume of that security to determine how easily or difficult it would be to find a buyer for your shares if you wanted to sell them.

For example, VOO, the Vanguard S&P 500 Index ETF has an average trading volume right now about 5 million shares and as the current share price is about $2.6 Billion in activity each day, there is a high probability that if you wanted to sell $500,000 of your VOO, that order could be easily filled. If instead, you are holding a very thinly traded ETF that only has an average trading volume of 100,000 share per day and you are holding 300,000 shares, it may take you a few days or weeks to sell your position and your activity could negatively impact the price as you try to sell because it could move the market with your trade given the light trading volume. Or worse, there is no one interested in buying your shares, so you are stuck with them. You just have to do your homework when investing the more thinly traded ETFs.

Passive & Active ETFs

Similar to mutual funds, there are both passive and active ETF’s. Passive ETFs aim to replicate the performance of an existing index like the S&P 500 Index or a bond index, while active strategy ETFs are trying to outperform a specific index through the implementation of their investment strategy within the ETF.

About Michael……...

Hi, I’m Michael Ruger. I’m the managing partner of Greenbush Financial Group and the creator of the nationally recognized Money Smart Board blog . I created the blog because there are a lot of events in life that require important financial decisions. The goal is to help our readers avoid big financial missteps, discover financial solutions that they were not aware of, and to optimize their financial future.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

How do ETFs differ from mutual funds in how they trade?

Mutual funds trade once per day at their net asset value (NAV) after the market closes, while ETFs trade throughout the day on stock exchanges at market prices. This gives ETF investors the ability to buy or sell shares at real-time prices, offering more flexibility and control.

Why are ETFs considered more tax-efficient than mutual funds?

ETFs are structured so that shares are exchanged between investors rather than redeemed by the fund itself. This means ETFs typically do not have to sell underlying securities to meet redemptions, helping investors avoid unexpected capital gains distributions that are common with mutual funds.

Are ETFs better suited for taxable or retirement accounts?

ETFs tend to be more tax-efficient, which makes them especially advantageous in taxable brokerage accounts. In tax-deferred retirement accounts like IRAs or 401(k)s, the tax efficiency difference between ETFs and mutual funds is less significant.

Why are mutual funds still common in 401(k) plans?

Mutual funds can trade in fractional shares, allowing every dollar of an employee’s contribution to be invested immediately. Most ETFs trade only in whole shares, which can leave small amounts of uninvested cash in retirement plans with frequent payroll contributions.

Do ETFs have minimum investment requirements?

Unlike many mutual funds that require a minimum initial investment, ETFs typically have no such minimums beyond the cost of a single share. This makes ETFs more accessible to investors who want to start with smaller amounts.

What risks should investors consider when buying ETFs?

One key risk is liquidity. Thinly traded ETFs may be harder to sell quickly or at a favorable price, especially for large positions. Checking an ETF’s average daily trading volume can help investors assess how easily they can enter or exit a position.

When Should High-Income Earners Max Out Their Roth 401(k) Instead of Pre-tax 401(k)?

While pre-tax contributions are typically the 401(k) contribution of choice for most high-income earners, there are a few situations where individuals with big incomes should make their deferrals contribution all in Roth dollars and forgo the immediate tax deduction.

While pre-tax contributions are typically the 401(k) contribution of choice for most high-income earners, there are a few situations where individuals with big incomes should make their deferral contributions all in Roth dollars and forgo the immediate tax deduction.

No Income Limits for Roth 401(k)

It’s common for high income earners to think they are not eligible to make Roth deferrals to their 401(k) because their income is too high. However, unlike Roth IRAs that have income limitations for making contributions, Roth 401(k) contributions have no income limitation.

401(k) Deferral Aggregation Limits

In 2025, the employee deferral limits are $23,500 for individuals under the age of 50, $31,000 for individuals aged 50-59 and 64 and older and $34,750 for individuals age 60-63. If your 401(k) plan allows Roth deferrals, the annual limit is the aggregate between both pre-tax and Roth deferrals, meaning you are not allowed to contribute $23,500 pre-tax and then turn around and contribute $23,500 Roth in the same year. It’s a combined limit between the pre-tax and Roth employee deferral sources in the plan.

Scenario 1: Business Owner Has Abnormally Low-Income Year

Business owners from time to time will have a tough year for their business. They may have been making $300,000 or more per year for the past year but then something unexpected happens or they make a big investment in their business that dramatically reduces their income from the business for the year. We counsel these clients to “never waste a bad year for the business”.

Normally, a business owner making over $300,000 per year would be trying to max out their pre-tax deferral to their 401(K) plans in an effort to reduce their tax liability. But, if they are only showing $80,000 this year, placing a married filing joint tax filer in the 12% federal tax bracket, I’ll ask, “When are you ever going to be in a tax bracket below 12%?”. If the answer is “probably never”, then it an opportunity to change the tax plan, max out their Roth deferrals to the 401(k) plan, and realize that income at their abnormally lower rate. Plus, as the Roth source grows, after age 59 ½ they will be able to withdrawal the Roth source ALL tax free including the earnings.

Scenario 2: Change In Employment Status

Whenever there is a change in employment status such as:

Retirement

High income spouse loses a job

Reduction from full-time to part-time employment

Leaving a high paying W2 job to start a business which shows very little income

All these events may present an abnormally low tax year, similar to the business owner that experienced a bad year for the business, that could justify the switch from pre-tax deferrals to Roth deferrals.

The Value of Roth Compounding

I’ll pause for a second to remind readers of the big value of Roth. With pre-tax deferrals, you realize a tax benefit now by avoiding paying federal or state income taxes on those employee deferrals made to your 401(k) plan. However, you must pay tax on those contributions AND the earnings when you take distributions from that account in retirement. The tax liability is not eliminated, just deferred.

Scenario 3: Too Much In Pre-Tax Retirement Accounts Already

When high income earners have been diligently saving in their 401(k) plan for 30 plus years, sometimes they amass huge pre-tax balances in their retirement plans. While that sounds like a good thing, sometimes it can come back to haunt high-income earnings in retirement when they hit their RMD start date. RMD stands for required minimum distribution, and when you reach a specific age, the IRS forces you to begin taking distributions from your pre-tax retirement account whether you need to our not. The IRS wants their income tax on that deferred tax asset.

The RMD start age varies depending on your date of birth but right now the RMD start age ranges from age 73 to age 75. If for example, you have $3,000,000 in a Traditional IRA or pre-tax 401(k) and you turn age 73 in 2025, your RMD for 2025 would be $113,207. That is the amount that you would be forced to withdrawal out of your pre-tax retirement account and pay tax on. In addition to that income, you may also be showing income from social security, investment income, pension, or rental income depending on your financial picture at age 73.

If you are making pre-tax contributions to your retirement now, normally the goal is to take that income off that table now and push it into retirement when you will hopefully be in a lower tax bracket. However, if your pre-tax balances become too large, you may not be in a lower tax bracket in retirement, and if you’re not going to be in a lower tax bracket in retirement, why not switch your contributions to Roth, pay tax on the contributions now, and then you will receive all of the earning tax free since you will now have money in a Roth source.

Scenario 4: Multi-generational Wealth

It’s not uncommon for individuals to engage a financial planner as they approach retirement to map out their distribution plan and verify that they do in fact have enough to retire. Sometimes when we conduct these meetings, the clients find out that not only do they have enough to retire, but they will not need a large portion of their retirement plan assets to live off and will most likely pass it to their kids as inheritance.

Due to the change in the inheritance rules for non-spouse beneficiaries that inherit a pre-tax retirement account, the non-spouse beneficiary now is forced to deplete the entire account balance 10 years after the decedent has passed AND potentially take RMDs during the 10- year period. Not a favorable tax situation for a child or grandchild inheriting a large pre-tax retirement account.

If instead of continuing to amass a larger pre-tax balance in the 401(k) plan, say that high income earner forgoes the tax deduction and begins maxing out their 401K contributions at $31,000 per year to the Roth source. If they retire at age 65, and their life expectancy is age 90, that Roth contribution could experience 25 years of compounding investment returns and when their child or grandchild inherits the account, because it’s a Roth IRA, they are still subject to the 10 year rule, but they can continue to accumulate returns in that Roth IRA for another 10 years after the decedent passes away and then distribute the full account balance ALL TAX FREE. That is super powerful from a tax free accumulate standpoint.

Very few strategies can come close to replicating the value of this multigenerational wealth accumulation strategy.

One more note about this strategy, Roth sources are not subject to RMDs. Unlike pre-tax retirement plans which force the account owner to begin taking distributions at a specific age, Roth accounts do not have an RMD requirement, so the money can stay in the Roth source and continue to compound investment returns.

Scenario 5: Tax Diversification Strategy

The pre-tax vs Roth deferrals strategy is not an all or nothing decision. You are allowed to allocate any combination of pre-tax and Roth deferrals up to the annual contribution limits each year. For example, a high-income earner under the age of 50 could contribute $13,000 pre-tax and $10,500 Roth in 2025 to reach the $23,500 deferral limit.

Remember, the pre-tax strategy assumes that you will be in lower tax bracket in retirement than you are now, but some individuals have the point of view that with the total U.S. government breaking new debt records every year, at some point they are probably going to have to raise the tax rates to begin to pay back our massive government deficit. If someone is making $300,000 and paying a top Fed tax rate of 24%, even if they expect their income to drop in retirement to $180,000, who’s to say the tax rate on $180,000 income in 20 years won’t be above the current 24% rate if the US government needs to generate more tax return to pay back our national debt?

To hedge against this risk, some high-income earnings will elect to make some Roth deferrals now and pay tax at the current tax rate, and if tax rates go up in the future, anything in that Roth source (unless the government changes the rules) will be all tax free.

About Michael……...

Hi, I’m Michael Ruger. I’m the managing partner of Greenbush Financial Group and the creator of the nationally recognized Money Smart Board blog . I created the blog because there are a lot of events in life that require important financial decisions. The goal is to help our readers avoid big financial missteps, discover financial solutions that they were not aware of, and to optimize their financial future.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

Can high-income earners make Roth 401(k) contributions?

Yes. Unlike Roth IRAs, Roth 401(k)s have no income limits for eligibility, meaning even high earners can make Roth contributions through their employer’s retirement plan if the plan allows them.

When might it make sense for a high-income earner to choose Roth 401(k) contributions?

Roth contributions can make sense during years of unusually low income or reduced tax brackets — such as a down business year or a job change — since the tax cost of contributing after-tax dollars is lower. These contributions can then grow tax-free for retirement.

How do Roth 401(k) and pre-tax 401(k) contributions differ in taxation?

Pre-tax 401(k) contributions lower taxable income now but are taxed upon withdrawal. Roth 401(k) contributions are made with after-tax dollars, but both contributions and earnings can be withdrawn tax-free in retirement if certain conditions are met.

What happens if you already have large pre-tax retirement balances?

Having too much in pre-tax accounts can lead to large required minimum distributions (RMDs) and higher taxable income in retirement. Switching future contributions to Roth can help balance tax exposure and reduce the impact of RMDs later.

Why might Roth 401(k)s be beneficial for multi-generational wealth planning?

Roth accounts are not subject to RMDs during the account owner’s lifetime and can be passed to heirs who can continue to grow the funds tax-free for up to 10 years. This makes Roth assets a powerful tool for tax-efficient inheritance planning.

Can you combine Roth and pre-tax 401(k) contributions?

Yes. Employees can split their deferrals between Roth and pre-tax sources in any ratio, as long as the combined total does not exceed annual IRS limits. This approach provides tax diversification and flexibility in managing future tax risk.

Why might tax diversification be valuable for retirement planning?

Future tax rates are uncertain, especially given rising government debt levels. Having both pre-tax and Roth sources allows retirees to draw income strategically depending on future tax environments.

How Will The Fed’s 50bps Rate Cut Impact The Economy In Coming Months?

The Fed cut the Federal Funds Rate by 0.50% on September 18, 2024 which is not only the first rate cut since the Fed started raising rates in March 2022 but it was also a larger rate cut than the census expected. The consensus going into the Fed meeting was the Fed would cut rates by 0.25% and they doubled it. This is what the bigger Fed rate cut historically means for the economy

The Fed cut the Federal Funds Rate by 0.50% on September 18, 2024, which is not only the first rate cut since the Fed started raising rates in March 2022, but it’s also a larger rate cut than most economists predicted. The consensus going into the Fed meeting was that the Fed would cut rates by 0.25%, and they doubled it. In this article, we will cover:

How is the stock market likely to respond to this larger than anticipated rate cut?

How is this rate cut expected to impact the economy in the coming months?

Do we expect this rate cut trend to continue in the coming months?

Recession trends when the Fed begins cutting rates.

How Rate Cuts Impact The Economy

When the Fed decreases the Federal Funds Rate, it is essentially breathing oxygen back into the economy. Even the anticipation of the Fed lowering rates has an impact on the interest rate on car loans, mortgages, and commercial lending. As interest rates move lower, it usually stimulates the economy by making financing more attractive to the U.S. consumer. For example, a new homebuyer may not be able to afford a new house if it’s financed with a 30-year mortgage with a 7.5% interest rate, but as interest rates move lower, to say 6%, it lowers the monthly mortgage payments, putting the house in reach for that new homebuyer.

6 Month Delay

The reason why we support the Fed making a bigger rate cut now is the inflation rate has moved into the Feds 2% to 3% range, the job market has been cooling over the past few months, evident in the unemployment rate rising, and when the Fed cuts rates, it takes 6 to 9 months before that rate cut translates to more economic activity because it takes time for the impact of those lower interest rates to work their way through the economy.

Historically, The Fed Waits Too Long To Cut Rates

It’s reassuring to see the Fed cutting rates before we see significant pain in the U.S. economy because that is not the typical Fed pattern. Historically, the Fed waits too long to begin cutting rates, and only after a recession has arrived from rates being held high for too long does the Fed begin cutting rates. However, then there is a 6-month lag before the economy feels the benefits of those rate cuts and it’s usually an ugly 6 months for the equity market. The fact that the Fed is cutting rates now and by a larger amount than the consensus expects increases the chances that a soft landing will be delivered to the economy coming out of this rate hike cycle.

Not Out of The Woods Yet

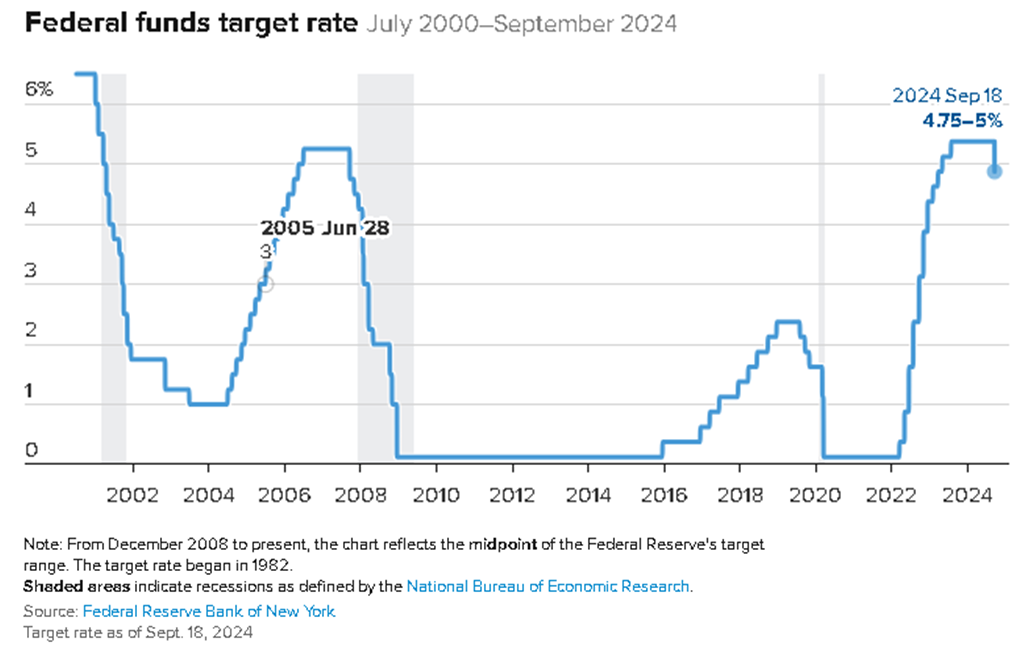

While the Fed proactively cutting rates is a positive sign in the short term, if we look at a historic chart of the Fed Funds Rate going back to 2000, you will see a pattern from past cycles that only AFTER the Fed begins cutting rates does the economy enter a recession. So, while we applaud the Fed for being proactive with these bigger rate cuts, it still echoes the warning, “Will this rate cut and the future rate cuts be enough to avoid a recession?”. Only time will tell.

Do We Expect Additional Fed Rate Cuts

We do expect the Fed to implement additional rate cuts before the end of 2024, which if the economy hits a rough patch within the next few months, will hopefully provide some optimism that help is already on the way as these rates cuts that have already been made work their way through the economy.

The good news is they have room to cut rates by more. We were concerned at the beginning of the rate hike cycle that if they were not able to raise rates by enough, they would not have enough room to cut rates if the economy ran into a soft patch; but given the magnitude of the rate hikes between March 2022 and now, there is plenty of room to cut and restore confidence if it is needed in coming months.

COVID Stimulus Money Still In The Economy

In general, I think individuals underestimate the power of the amount of cash that was pumped into the system during COVID that was never taken out. In the 2008/2009 recession, the Federal Reserve expanded its balance sheet by about $1 trillion. During COVID they expanded the Fed balance sheet by about $4.5 Trillion, and to date they have only taken back about $1T of the initial $4.5T, so the U.S. economy has an additional $3.5T in liquidity that was not in the economy before 2020. That’s a lot of money to build a bridge to a possible soft-landing scenario.

Multiple Forces Acting On The Markets

We do expect escalated levels of volatility in the stock market in the fourth quarter. Not only do we have the market volatility surrounding the change in Fed policy, but we also have the elections in November that will inevitably inject additional volatility into the markets. As we get past the elections and enter 2025, we may return to more normal levels of volatility, because at that point the economy will know the political agenda for the next 4 years and some of the Fed rate cuts will have worked their way into the economy, potentially leading to stronger economic data in Q1 and Q2 of 2025.

All eyes will be on the race between the Fed rate cuts and the health of the economy.

About Michael……...

Hi, I’m Michael Ruger. I’m the managing partner of Greenbush Financial Group and the creator of the nationally recognized Money Smart Board blog . I created the blog because there are a lot of events in life that require important financial decisions. The goal is to help our readers avoid big financial missteps, discover financial solutions that they were not aware of, and to optimize their financial future.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

Why did the Federal Reserve cut rates by 0.50% in September 2024?

The Fed cut the Federal Funds Rate by 0.50% to support a slowing economy as inflation returned to its target range and the job market began to cool. The larger-than-expected cut was intended to provide earlier stimulus rather than waiting until the economy weakens further.

How do Fed rate cuts typically affect the economy?

Lowering interest rates makes borrowing cheaper for consumers and businesses, which can boost spending on homes, cars, and investments. However, it typically takes six to nine months for the effects of a rate cut to fully work through the economy.

Should You Buy or Lease A Car?

The most common questions that I receive when clients are about to purchase their next car is “should I buy it or lease it?” The answer depends on a number of factors including how long do you typically keep cars for, how many miles do you drive each year, the amount of the down payment, maintenance considerations, or do you have any teenagers in the family that will be driving soon?

The most common questions that I receive when clients are about to purchase their next car is, “Should I buy it or lease it?” The answer depends on the following items:

How long do you typically keep cars for?

How many miles do you drive each year?

Amount of the down payment

Maintenance considerations

Do you have any teenagers in the family that will be driving soon?

When Should You Lease A Car?

Let’s start with the lease scenario. The leasing approach tends to favor individuals that keep their cars for less than 5 years and don’t drive a lot of miles each year. The duration of ownership matters because most cars are considered depreciating assets, meaning they decrease in value over time, and the lion share of depreciation on a new car typically happens within the first few years.

Example: If you buy a brand-new car for $40,000 and a year or two from now if you wanted to sell that car, you would receive less than $40,000. You may only receive $35,000 or $30,000 depending on how well the type of car you purchased holds its value which varies from car to car.

If you are the type of person that likes driving a new car every 3 years and you were to buy the car instead of lease it, you are incurring the lion share of the depreciation in value every time you buy a new car and then trade it in or sell it every few years. When you lease a car, you technically do not own it, you are borrowing it from the dealer, and you are entering a contract with the dealer that specifies how long you are allowed to borrow the car, the mileage allowance, and the buyout price at the end of the lease.

When the car lease is over, you drive the car back to the dealer, hand them the keys, and you don’t have to worry about what the trade in value will be. If you decide you want to buy the car at the end of your lease, the lease contract typically has a set purchase amount that you are allowed to buy the car from at the end of the 3-year lease term.

Mileage Matters

When you enter into a car lease, there is usually a mileage allowance listed in your contract that states the number of miles you are allowed to log on the odometer during the duration of the lease agreement. Most 3-year lease agreements provide a 10,000 to 15,000 mileage allowance each year, so your 3-year lease agreement may be limited to 30,000 miles during the duration of the lease. If you go over that mileage allowance, there are usually fairly steep mileage penalties that you have to pay at the end of the lease agreement. Typically, those milage fees can be $0.10 to $0.30 per mile.

Example: If your 3-year lease has a 30,000-mileage allowance, but you drive more miles than expected and turn in the car with 40,000 miles at the end of the 3 year period with a mileage penalty of $0.25 per mile in your lease agreement, you would owe the dealer $2,500 when you go to turn in your car.

When individuals go way over their mileage allowance, instead of just handing the dealer a big chunk of cash, and then not having a car, you may have the option to take out car loan at the end of the lease and buy the car from the dealer at the set price listed in your lease agreement.

Leasing Risks for Young Professionals

I think mileage is one of the bigger risks when leasing a car, especially for young individuals that are just entering the work force. Why? Because life and careers tend to change at a rapid pace between the ages of 20 and 40. These young professionals may be working for an employer now that allows them to work fully remote, so they put minimal mileage on their car and decide that leasing the car is the way to go. However, what happens when that individual is offered a much better job that requires them to go into an office setting and the office is 30 miles from their apartment? Now, they are going to start logging more miles on their car which could put them over the mileage allowance in the lease.

Lease: No Down Payment

The first two questions that the car salesman asks you when you enter a dealership is:

What were thinking about for a monthly payment?

How much were you planning on putting down on the car as a down payment?

If you want to buy a new car, in most cases, buying the car versus leasing the car is going to be more expensive out of the gates because remember, when you buy the car you own it and when you lease the car you don’t own it, you are just borrowing it. With a lease, since you don’t own the car, they may offer a new car with no down payment, and the payments may be lower than buying the car outright…..again…..because you don’t own it. Your monthly payments just go directly to the financing company without you ever owning anything. It’s a similar concept as renting an apartment vs buying a house.

However, if you typically trade in your cars every three years for the newer model, as long as you can stay within the mileage allowance, leasing could make sense because unlike a house that’s an appreciating asset (which means it gains value over time), a car is a depreciating asset which loses value over time. So, if you are trading in cars every three years with the benefit of realizing a loss in value every three years, it may be better to borrow the car and use your additional cash to meet other financial goals.

Maintenance Costs

When you lease a car, often times it removes the risk of incurring big costs associated with fixing the vehicle if something major goes wrong. It’s common for the lessee to be responsible for routine maintenance like oil changes, but leased cars are typically new and covered under warrantee for most major issues that could arise.

When Should You Buy A Car Instead of Leasing?

Now onto the buy section. When should you buy a car instead of lease it? The first question I always ask is how long do you drive your cars for? If someone says 5 years or more, it almost always favors buying the car instead of leasing it. While you will have a little more cost up front, because purchasing a car usually requires a downpayment, you open the opportunity to visit the land of “No Car Payments”.

For anyone that has been to the “Land of No Car Payments” it’s wonderful. If you enter into a 5-year car loan and you drive that car for 8 years, you have 3 years of no car payments. It’s like driving a car for free. With a lease you will technically always have a car payment, even if you front all the money at the beginning of the lease, because you never own the car. At the end of the 3rd year, you still have to buy it at a price that may be above what the market value of that car is at the end of the lease.

The car still depreciates in value but if you own a car for 6 years and have 120,000 miles on the car, as long as you have taken care of it over that 6 year period, you car will typically still have value, so when you go to trade it in to buy your next car, you down payment may already be covered by the trade in value.

You Drive A Lot

If you drive a lot, whether for work, pleasure, or both, it tends to favor buying a car because it’s unlikely you would be able to stay within the mileage allowance of a lease, and big mileage penalties would be waiting for you at the end of the lease agreement.

Buying A Car: Bigger Down Payment & Higher Monthly Payments

We covered this topic in the leasing section but it’s worth repeating. It can be very tempting to enter into a lease since there may be no downpayment, a low monthly lease payment, which may get you into a newer or nicer car, and all too often people underestimate how much they drive each year mileage wise. While you may work for home, how many miles do you drive taking the kids back and forth to school, practices, dinners, friends houses, family vacations, grocery store runs, meeting friends for dinner, etc. Unless you have owned cars for a number of years, and life is relatively unchanged compared to past years, it often tough to judge how many miles you will log on that car over the next 3 years outside of the life surprises like moving or changing careers.

Buying a car and not having to worry about staying within a mileage allowance takes that financial risk off the table.

Car Maintenance

When you own a car, you have the option of buying extended warranties which adds to your monthly payments on the vehicle. These become a personal preference of whether or not these extended warranties are worth the money, but if you opt not to go with robust extended warranties, you have to make sure that you have enough cash reserved in case your vehicle requires an expensive repair that’s not covered by warranty after the first number of years, that you will have the cash to pay for it. It just takes some extra planning on the part of the car owner.

Teenage Driving Soon

When I'm consulting with clients that are about to buy a new car and have children between the ages of 12 and 16, I'll sometimes ask the question, “What's the plan for when their child turns 16 and begins driving?”. Depending on the type of car they're buying, would it potentially be a long term financial planning move for the parent to buy the car, drive it for four to six years, and then when their child gets their driver’s license, they have a used car that has been paid off, taken care of, ready to go, and then the parent can go out an get a new car at the time of the hand off. It’s a plan that has worked well for several clients which favors buying the car versus leasing.

Avoid 6 to 8 Year Car Loans

We have seen a rapid rise and the number of consumers that are taking car loans with a duration of six to eight years. The conventional auto loan used to be five years, and nothing beyond that was offered, but now we see car dealerships starting the conversation at a seven-year car loan in an effort to make the monthly payments lower. However, this created a new problem called the negative equity trap. Since, again, a car is a depreciating asset, it loses value over time, and if at the time you go to trade it in the loan outstanding on the car is higher than the value of the car itself, you get stuck in what’s called a negative equity event, where the outstanding car loan is higher than the value of the car.

Auto dealers will often address this by allowing you to roll over your negative equity to your next car. Meaning if you're upside down by $3000 when you go to trade in your car and you buy the new car for $40,000, the car loan will be for $43,000. The problem is, your negative equity problem just got larger with the next car because you're already starting at a higher loan amount than what the car is worth. If you do this a few times people will sometimes reach a situation where the negative equity amount has become so large that banks will no longer allow them to roll that into the next car loan and they get stuck.

When buying a car, I often encourage individuals to avoid the temptation of the six to eight-year car loan and stick with the five year conventional auto loan to avoid these negative equity events.

What Does The Investment Advisor Do?

Sometimes my clients will ask me “Mike, what do you do?” I’m a buyer of cars mainly becuase I drive a lot miles each year and I typically keep cars for 7 to 8 years. But if I was an individual that drove under 12,000 mile each year and enjoyed trading in my cars every 3 years, then I could see how leasing would make sense. The decision to buy or lease truly depends on the travel habits, ownership duration, debt preferences, budget, and new or used car preference of each individual buyer.

About Michael……...

Hi, I’m Michael Ruger. I’m the managing partner of Greenbush Financial Group and the creator of the nationally recognized Money Smart Board blog . I created the blog because there are a lot of events in life that require important financial decisions. The goal is to help our readers avoid big financial missteps, discover financial solutions that they were not aware of, and to optimize their financial future.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

What factors determine whether leasing or buying a car makes more sense?

The decision depends on how long you keep cars, how many miles you drive each year, your down payment amount, maintenance preferences, and whether other drivers—like teenagers—will soon use the vehicle. Each of these factors influences both cost and convenience over time.

When does leasing a car make financial sense?

Leasing is best for drivers who keep cars for less than five years and drive fewer than 12,000–15,000 miles annually. It allows you to drive a new car with lower monthly payments and minimal maintenance costs, while avoiding long-term depreciation.

What are the downsides of leasing a car?

Exceeding mileage limits can result in costly penalties, often 10–30 cents per mile. You also don’t build ownership equity—once the lease ends, you return the vehicle or pay the preset buyout amount, which may be higher than the market value.

Who should consider buying instead of leasing?

Buying generally makes more sense if you keep cars for more than five years or drive high mileage. Once the car loan is paid off, you can enjoy years without car payments, and the vehicle still retains trade-in value.

Why should you avoid long car loans?

Car loans lasting six to eight years can lead to negative equity, where the loan balance exceeds the car’s value. Sticking to a traditional five-year loan reduces this risk and helps prevent carrying debt into your next vehicle purchase.

How can buying a car help families with teenage drivers?

Parents planning ahead can buy and maintain a vehicle for several years, then pass it down when a child begins driving. This approach can reduce future car costs and provide a reliable, paid-off vehicle for the new driver.

How do maintenance and warranty costs differ between buying and leasing?

Leased cars are typically under warranty for major repairs, with the lessee responsible only for routine maintenance. Buyers must plan for potential out-of-warranty repairs later in ownership but have the option to purchase extended coverage.

How Much Should I Contribute to Retirement?

A question I’m sure to address during employee retirement presentations is, “How Much Should I be Contributing?”. In this article, I will address some of the variables at play when coming up with your number and provide detail as to why two answers you will find searching the internet are so common.

A question I’m sure to address during employee retirement presentations is, “How Much Should I be Contributing?”. Quick internet search led me to two popular answers.

Whatever you need to contribute to get the match from the employer,

10-15% of your compensation.

As with most questions around financial planning, the answer should really be, “it depends”. We all know it is important to save for retirement, but knowing how much is enough is the real issue and typically there is more work involved than saying 10-15% of your pay.

In this article, I will address some of the variables at play when coming up with your number and provide detail as to why the two answers previously mentioned are so common.

Expenses and Income Replacement

Creating a budget and tracking expenses is usually the best way to estimate what your spending needs will be in retirement. Unfortunately, this is time-consuming and is becoming more difficult considering how easy it is to spend money these days. Automatic payments, subscriptions, payment apps, and credit cards make it easy to purchase but also more difficult to track how much is leaving your bank accounts.

Most financial plans we create start with the client putting together an itemized list of what they believe they spend on certain items like clothes, groceries, vacations, etc. A copy of our expense planner template can be found here. These are usually estimates as most people don’t track expenses in that much detail. Since these are estimates, we will use household income, taxes, and bank/investment accounts as a check to see if expenses appear reasonable.

What do expenses have to do with contributions to your retirement account now? Throughout your career, you receive a paycheck and use those funds to pay for the expenses you have. At some point, you no longer have the paycheck but still have the expenses. Most retirees will have access to social security and others may have a pension, but rarely does that income cover all your expenses. This means that the shortfall often comes from retirement accounts and other savings.

Not taking taxes, inflation, or investment gains into account, if your expenses are $50,000 per year and Social Security income is $25,000 a year, that is a $25,000 shortfall. 20 years of retirement times a $25,000 shortfall means $500,000 you’d need saved to fund retirement. Once we have an estimate of the coveted “What’s My Number?” question, we can create a savings plan to try and achieve that goal.

Cash Flow

As we age, some of the larger expenses we have in life go away. Student loan debt, mortgages, and children are among those expenses that stop at some point in most people’s lives. At the same time, your income is usually higher due to experience and raises throughout your career. As expenses potentially go down and income is higher, there may be cash flow that frees up allowing people to save more for retirement. The ability to save more as we get older means the contribution target amount may also change over time.

Timing of Contributions

Over time, the interest that compounds in retirement accounts often makes up most of the overall balance.

For example, if you contribute $2,000 a year for 30 years into a retirement account, you will end up saving $60,000. If you were able to earn an annual return of 6%, the ending balance after 30 years would be approximately $158,000. $60,000 of contributions and $98,000 of earnings.

The sooner the contributions are in an account, the sooner interest can start compounding. This means, that even though retirement saving is more cash flow friendly as we age, it is still important to start saving early.

Contribute Enough to Receive the Full Employer Match

Knowing the details of your company’s retirement plan is important. Most employers that sponsor a retirement plan make contributions to eligible employees on their behalf. These contributions often come in the form of “Non-Elective” or “Matching”.

Non-Elective – Contributions that will be made to eligible employees whether employees are contributing to the plan or not. These types of contributions are beneficial because if a participant is not able to save for retirement from their own paycheck, the company will still contribute. That being said, the contribution amount made by the employer, on its own, is usually not enough to achieve the level of savings needed for retirement. Adding some personal savings in addition to the employer contribution is recommended.

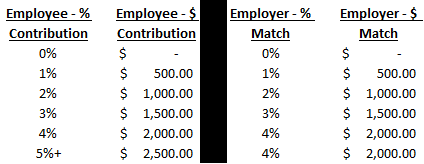

Matching – Employers will contribute on behalf of the employee if the employee is contributing to the plan as well. This means if the employee is contributing $0 to the retirement plan, the company will not contribute. The amount of matching varies by company, so knowing “Match Formula” is important to determine how much to contribute. For example, if the matching formula is “100% of compensation up to 4% of pay”, that means the employer will contribute a dollar-for-dollar match until they contribute 4% of your compensation. Below is an example of an employee making $50,000 with the 4% matching contribution at different contribution rates.

As you can see, this employee could be eligible for a $2,000 contribution from the employer, if they were to save at least 4% of their pay. That is a 100% return on your money that the company is providing.

Any contribution less than 4%, the employee would not be taking advantage of the employer contribution available to them. I’m not a fan of the term “free money”, but that is often the reasoning behind the “Contribute Enough to Receive the Full Employer Match” response.

10%-15% of Your Compensation

As said previously, how much you should be contributing to your retirement depends on several factors and can be different for everyone. 10%-15% over a long-term period is often a contribution rate that can provide sufficient retirement savings. Math below…

Assumptions

Age: 25

Retirement Age: 65

Current Income: $30,000

Annual Raises: 2%

Social Security @ 65: $25,000

Annualized Return: 6%

Step 1: Estimate the Target Balance to Accumulate by 65

On average, people will need an estimated 90% of their income for early retirement spending. As we age, spending typically decreases because people are unable to do a lot of the activities we typically spend money on (i.e. travel). For this exercise, we will assume a 65-year-old will need 80% of their income throughout retirement.

Present Salary - $30,000

Future Value After 40 Years of 2% Raises - $65,000

80% of Future Compensation - $52,000

$52,000 – income needed to replace

$25,000 – social security @ 65

$27,000 – amount needed from savings

X 20 – years of retirement (Age 85 - life expectancy)

$540,000 – target balance for retirement account

Step 2: Savings Rate Needed to Achieve $540,000 Target Balance

40 years of a 10% annual savings rate earning 6% interest per year, this person could have an estimated balance of $605,000. $181,000 of contributions and $424,000 of compounded interest.

I hope this has helped provide a basic understanding of how you can determine an appropriate savings rate for yourself. We recommend reaching out to an advisor who can customize your plan based on your personal needs and goals.

About Rob……...

Hi, I’m Rob Mangold, Partner at Greenbush Financial Group and a contributor to the Money Smart Board blog. We created the blog to provide strategies that will help our readers personally, professionally, and financially. Our blog is meant to be a resource. If there are questions that you need answered, please feel free to join in on the discussion or contact me directly.

What Happens When A Minor Child Inherits A Retirement Account?

There are special non spouse beneficiary rules that apply to minor children when they inherit retirement accounts. The individual that is assigned is the custodian of the child, we'll need to assist them in navigating the distribution strategy and tax strategy surrounding they're inherited IRA or 401(k) account. Not being aware of the rules can lead to IRS tax penalties for failure to take requirement minimum distributions from the account each year.

There are special non-spouse beneficiary rules that apply to minor children when they inherit retirement accounts. The individual who is assigned as the custodian of the child will need to assist them in navigating the distribution strategy and tax strategy surrounding their inherited IRA or 401(k) account. Not being aware of the rules can lead to IRS tax penalties for failure to take the required minimum distributions from the account each year.

Minor Child Rule After December 31, 2019

Congress changed the rules for minor children as beneficiaries of retirement accounts when they passed the Secure Act in 2019. If the Minor child inherits a retirement account from someone who passes away after December 31, 2019, the minor child is subject to the new nonspouse beneficiary rules associated with the new tax law. The new tax law creates a blend of the old “stretch rule” and the new 10-year rule for children that inherit retirement accounts. It also matters who the child inherited the account from - a parent, or someone other than a parent.

Minor Child Inherits Retirement Account From A Parent

If a minor child inherits a retirement account from their parents, and the parent that they inherited the account from passed away after December 31, 2019, the minor child will need to move the 401(k) or IRA into an Inherited IRA before December 31st of the year after their parent passes away, and then begin taking annual Required minimum distributions (RMDs) from the inherited IRA each year until they reach age 21. Once they reach age 21, they are then subject to the 10-year rule, which requires the minor to fully deplete the account within 10 years of turning age 21.

Age of Majority is 21

Different states have different ages of majority, some 18 and others 21. But the IRS released clarifying final regulations in July 2024, stating that for purposes of minor children moving from the annual RMD requirement to the 10-year rule would be the age of 21 regardless of the state the child lives in and regardless of whether or not the child is a student after age 18.

Here is an example: Richard passes away in a car accident in March 2024, the sole beneficiary of his 401 (k) at work is his 10-year-old daughter, Kelly. Kelly’s guardian would need to assist her with setting up an inherited IRA before December 31, 2025, and rollover Richard’s 401K balance into that Inherited IRA account. Since Kelly is under the age of 21, she would be required to take annual required minimum distributions from the account, which are calculated based on her age and an IRS life expectancy table beginning in 2025. When she receives those annual RMDs for the Inherited IRA, she has to pay income tax on them, but does not incur a 10% early withdrawal penalty for being under the age of 59 1/2 since they are considered death distributes.

Kelly will need to continue to take those RMD's each year until she reaches age 21. At age 21, she is then subject to the new 10-year rule associated with non-spouse beneficiaries which requires her to fully deplete that inherited IRA balance within 10 years of reaching the age 21.

Tax Strategy For Inherited IRAs for Minors

The guardians of the minor child will need to assist them with the tax strategy associated with taking distributions from their inherited IRA account, since any money withdrawn from these accounts is considered taxable income to the child. While the IRS requires the minor child to take a small distribution each year to satisfy the annual RMD requirement, they are allowed to take any amount they would like out of the inherited IRA which creates a tax planning opportunity since most children have very little taxable income, and are in very low tax brackets.

However, distributions from inherited IRAs are considered “unearned income” subject to Kidde tax so the custodian’s of the minor’s inherited IRA have to be very careful of taking distribution above the current $2,700 amount which then triggers the Kiddie tax.

FAFSA Warning

Another factor to consider one taking distributions from a minor’s inherited IRA is the impact on their college financial aid if they are college bound after high school. Distributions from these inherited IRA accounts are considered income of the child which is the most punitive category within the college financial aid award formula. A child’s income, over a specific threshold, counts approximately 50% against any college financial aid that could potentially be awarded. So, if a child processes a distribution from their inherited IRA for $20,000, while it might be a good tax move, if that child would have qualified for need based college financial aid, they may have just lost $10,000 in aid due to that IRA distribution during a determination year.

When a FAFSA application is completed for a child, the determined year for income purposes of the financial aid award looks back 2 years, so there is a lot of advanced planning by the guardian of the child that needs to take place to make sure larger inherited IRA distributions do not adversely affect the FAFSA award.

Example: If the child will be entering college in the fall of 2025, the FAFSA calculations looks at their income from 2023 to determine how much college financial aid they qualify for.

Traditional IRA vs Roth IRA

It does matter whether the child inherits a Traditional IRA or a Roth IRA. The RMD rule and the 10-year rule are the same, but the taxation of the distributions from the IRA to the child are different. If the child has an Inherited Traditional IRA, the guardian has to be more careful about making distributions to the minor child because all distributions are considered taxable income. If the child has an Inherited Roth IRA, by nature of the Roth IRA rules the distributions are not taxable to the minor child. However, Roth IRA's are extremely valuable because all the accumulation within the inherited Roth IRA are tax free upon withdrawal, so typically the strategy is to keep the account intact as long as possible so the child receives as much tax free appreciation as possible at the end of the 10 years.

Minor Child 10-Year Rule

Once the child reaches age 21, the rules change to the 10-year rule, which requires the child to deplete any remaining balance in the inherited IRA within 10 years of turning age 21. The child has full discretion on the amounts that they wish to withdraw from their inherited IRA each year.

Minor Child Inherits A Retirement Account From A Non-Parent

If a minor child inherits a retirement account from someone other than their parents, the inherited IRA rules are different. The child is no longer allowed to take RMD’s from the inherited IRA each year until age 21, and then switch to the 10 year rule. If the child inherits a retirement account from someone other than their parent, they are treated the same as any other non-spouse beneficiary, and are immediately subject to the 10 year rule. They may or may not be required to take RMDs each year IN ADDITION to being required to deplete the account within 10 years, but that depends on what the age of the decedent was when they passed.

When the decedent passed away, if they had already reached their Required Beginning Date for RMDs, then the minor child would be required to continue to take annual RMD’s from the inherited IRA in addition to the 10-year rule starting immediately. If the decedent has yet to reach the required beginning date for RMDs, then the minor child is just subject to the 10-year rule.

In either situation, a minor child immediately subject to the 10-year rule requires detailed tax planning to avoid adverse and toxic consequences of poor distribution planning to avoid the loss of college financial aid due to the taxable income assigned to the child associated with those distributions from the inherited IRA.

About Michael……...

Hi, I’m Michael Ruger. I’m the managing partner of Greenbush Financial Group and the creator of the nationally recognized Money Smart Board blog . I created the blog because there are a lot of events in life that require important financial decisions. The goal is to help our readers avoid big financial missteps, discover financial solutions that they were not aware of, and to optimize their financial future.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

What are the special inheritance rules for minor children who inherit retirement accounts?

When a minor inherits a retirement account, the account must be transferred into an inherited IRA, and the child’s custodian must ensure required distributions are taken each year. The Secure Act of 2019 created specific rules for minors that combine annual required minimum distributions (RMDs) with the 10-year depletion rule once the child reaches age 21.

How do the inherited IRA rules differ if the minor inherits from a parent versus a non-parent?

If the child inherits from a parent, they must take annual RMDs until age 21 and then deplete the account within 10 years after turning 21. If the inheritance comes from someone other than a parent, the child is treated as a standard non-spouse beneficiary and must follow the 10-year rule immediately, with RMDs possibly required depending on the age of the deceased.

What did the 2024 IRS guidance clarify about the age of majority for inherited IRAs?

In July 2024, the IRS confirmed that for inherited IRA purposes, the age of majority is 21 nationwide, regardless of state laws or student status. This means the 10-year distribution clock begins when the child turns 21, not earlier.

How are inherited IRA distributions for minors taxed?

Distributions from inherited traditional IRAs are taxable income to the child, though they are exempt from early withdrawal penalties. These withdrawals count as unearned income and may trigger the Kiddie Tax if annual unearned income exceeds $2,700.

How can inherited IRA distributions affect college financial aid?

Withdrawals from an inherited IRA are counted as the child’s income for FAFSA purposes, which can significantly reduce need-based financial aid. Because FAFSA reviews income from two years prior, guardians should time distributions carefully to avoid lowering aid eligibility.

Do inherited Roth IRAs follow the same rules as inherited traditional IRAs?

Yes, both types are subject to RMD and 10-year rules, but Roth IRA distributions are tax-free. This makes inherited Roth IRAs especially valuable if left to grow for the full 10-year period, allowing for maximum tax-free appreciation.

What steps should guardians take when managing a minor’s inherited IRA?

Guardians should ensure the account is properly set up as an inherited IRA, monitor RMD compliance, and plan withdrawals to balance tax efficiency, Kiddie Tax exposure, and college aid implications. Proper planning helps avoid penalties and unnecessary loss of financial aid.

What Happens When You Inherit an Already Inherited IRA?

When you are the successor beneficiary of an Inherited IRA the rules are very complex.

When someone passes away and they have a retirement account, if there are non-spouse beneficiaries listed on the account, they will typically rollover the balance in the inherited retirement account to either an Inherited Traditional IRA or Inherited Roth IRA. But what happens when the original beneficiary passes away and there is still a balance remaining in that inherited IRA account? The answer is that a successor beneficiary inherits the account, and then the distribution rules become complex very quickly.

Beneficiary of an Inherited IRA (Successor Beneficiaries)

As a beneficiary of an inherited IRA, it's important to understand that the options available to you for taking distributions for the account will be determined by the distribution options that were available to the original beneficiary of the retirement account that you inherited it from, which vary from beneficiary to beneficiary.

Non-spouse Inherited IRA Rule

The IRS changed the rules for non-spouse beneficiaries back in 2019 with the passing of the Secure Act, which put original non-spouse beneficiaries in two camps: beneficiaries that inherited a retirement account from someone that passed away prior to January 1, 2020, and beneficiaries that inherited retirement accounts some someone that passed January 1, 2020 or later.

We have a whole article dedicated to these new non-spouse beneficiary rules that can be found on our website but for now I will move forward with the cliff notes version.

Stretch Rule vs 10-Year Rule Beneficiaries

As the beneficiary of an inherited IRA, you must be able to answer two questions:

Was the original beneficiary subject to the “RMD stretch rule” or “10-year rule”?

If that beneficiary was required to take an RMD in the year they passed, did they already distribute the full amount?

Original Beneficiary was the Spouse

A common situation is that a child has two parents - the first parent passes away, and the balance in those retirement accounts are then inherited by the surviving spouse and moved into the surviving spouse’s own retirement accounts. A spouse of an original owner of a retirement account has special rules available to them which allow them to roll their deceased spouse’s retirement accounts into their own retirement accounts and treat them as their own. When their children inherited the remaining balance in the retirement accounts from the second to parent, they are considered non spouse beneficiaries and are most likely subject to the new 10-year distribution rule unless they qualify for an exception.

Non-spouse Beneficiary 10-Year Rule

If the original beneficiary of the Inherited IRA received that account from someone that passed away after December 31, 2019 and they are a non-spouse beneficiary, they are most likely subject to the new 10-Year Rule which requires the original beneficiary to fully deplete that retirement within 10 year of the year following the original decedent’s death.

Example: Sue, the original owner of a Traditional IRA passes away in 2022, and her daughter Katie is the sole beneficiary of her IRA. Since Katie is a non-spouse beneficiary, she would be required to fully deplete the IRA by 2032, 10 years following the year after that Sue passed away.

But what happens if Katie, the original beneficiary of that inherited IRA passes away in 2026, and she is only 4 years into the 10-year depletion cycle? In this example, when Katie set up her inherited IRA, she named her two children Scott & Mara as 50/50 beneficiary on her inherited IRA account. Scott and Mara would move their respective 50% balance into their own inherited IRA account but as beneficiaries of an already inherited IRA, the 10-year rule does not reset. Scott & Mara would be bound to the same 10-year depletion date that Katie was subject to so Scott & Mara would have to deplete the Inherited IRA (2 times inherited) by 2032 which was Katie’s original 10-year depletion date.

10-Year Rule: The basic rule is if the original beneficiary of the inherited IRA was subject to the 10-year rule, as the new beneficiary of that existing inherited IRA, you get whatever time is remaining in that original 10-year period to fully deplete that Inherited IRA. It does not matter whether the inherited IRA that you inherited was a Traditional IRA or a Roth IRA, the same rules apply.

Original Beneficiary was a “Stretch Rule” beneficiary or the Spouse

For original non-spouse beneficiaries that inherited the retirement account from an account owner that passed away before January 1st, 2020, they have access to what is called the Stretch Rule. Those non-spouse beneficiaries are allowed to move the original owners balance of the retirement account to their own inherited IRA and they are not required to deplete the account in 10 years.

Instead, those non-spouse beneficiaries are only required to take an annual RMD (required minimum distribution) each year, which are small distributions from the Inherited IRA each year, but they could effectively stretch the existence of that inherited account over their lifetime. But it’s also important to note, that some non-spouse beneficiaries that inherited a retirement account from someone who passes on or after January 1, 2020, may have qualified for a stretch rule exception which are as follows:

Surviving spouse

Person less than 10 years younger than the decedent

Minor children

Disabled person

Chronically ill person

Some See-Through Trusts benefitting someone on this exception list

If the original beneficiary of the inherited IRA was eligible for the stretch rule, and you inherited that inherited IRA from that individual, you would NOT be eligible for the Stretch Rule, you would be subject to the 10-year rule, but you would have a full 10-years after the owner of that inherited IRA passes away to fully deplete the balance in that inherited IRA that you inherited.

When we are talking about beneficiaries of an already inherited IRA, it does not matter whether you were their spouse or non-spouse because the spouse exceptions only apply to the spouse of the original decedent.

Example: John inherited a Traditional IRA from his father who passed away in 2018. John was a non-spouse beneficiary, but since his father passed before 2020, he was eligible for the stretch provision which allowed John to roll over the Traditional IRA to an inherited IRA in his name and he was only required to take annual RMD’s each year but was not required to deplete the account in 10 years. John passes in 2025, his daughter Sarah is the beneficiary of the Inherited IRA, since Sarah inherited the inherited IRA from John who passes after December 31, 2019, Sarah would be required to deplete the balance in John’s inherited IRA by 2035, 10-year following the year after John passes.

RMD of Beneficiaries of Inherited IRAs

Now we have to move on to the second question that beneficiaries of Inherited IRAs need to ask, which is “does the successor beneficiary of an inherited IRA need to take annual RMD’s from the account each year?” The answer is “it depends”.

It’s common for beneficiaries of Inherited IRAs to be subject to both the 10-year rule and be required to take annual required minimum distributions from the account. Whether or not the beneficiary needs to take an RMD will depend on the whether or not the original beneficiary of the account was required to take RMDs. The basic rule is if the current owner of the Inherited IRA was required to take annual RMD’s from the account, you as the beneficiary of the Inherited will be required to continue to take RMD’s from the account. The IRS has a rule that once an owner of an IRA or Inherited IRA has started taking RMDs, they cannot be stopped.

If the answer is “Yes:”, the person that you inherited the Inherited IRA from was already taking RMD’s from the Inherited IRA account, then you as the beneficiary of that inherited IRA would be subject to whatever time is left in the 10-year rule, and you would also be required to take RMDs from the account each year.

Don’t Forget To Take The Decedent’s RMD

RMD’s are usually required to begin the year after an individual passes away which is true of Inherited IRAs but as the beneficiary of an retirement account, where the decedent was required to take an RMD for that year, you have to ask the question: did they satisfy their RMD requirement before they passed away.

If the answer is “yes”, no action is required in the year that they passed away unless they were in year 10 year of the depletion cycle.

If the answer is “no”, then you as the beneficiary of that existing Inherited IRA are required to take the undistributed RMD amount from that inherited IRA in the year that the decedent passed away.

Example: Kelly inherits an Inherited IRA from her mother Linda. Linda originally inherited the IRA from her father when he passed in 2022. At the time that her father passed, he was 80, which made him subject to RMDs. When Linda inherited the account from her father, since he was subject to RMDs, Linda was subject to the 10-year rule and annual RMDs. Linda passed in 2024, her daughter Kelly inherits her Inherited IRA, and Kelly would be required to fully deplete the inherited IRA by 2032 (Linda original 10 year rule date), she would be required to take annual RMD’s from the account because Linda was receiving RMDs, and if Linda did not receive her full RMD in 2024 when she passed, Kelly would have to distribute any amount that Linda would have been required to take in the year that she passes.

A lot of rules, but all very important to avoid the IRS penalties that await the taxpayers that fail to take the proper RMD amount or fail to adhere to the new 10-year rule.

Summary of 3 Successor IRA Questions

When you are the beneficiary of an inherited IRA, you must be able to answer the following questions:

Was the person that you inherited the inherited IRA from subject to the 10-year rule?

Was the person that you inherited the Inherited IRA from required to take annual RMDs?

Did the decedent take their RMD before they passed?

What was the age of the decedent when that passed?

The last question is important because there are potential situations where someone is the original beneficiary of an Inherited IRA subject to the 10-year rule, based on the age of the original owner when they passed and the age when the original beneficiary when they inherited the IRA may not make them subject to the annual RMD requirement. However, if the original beneficiary passes away after their “Required Beginning Date” for RMDs, the beneficiary of that inherited IRA may be subject to an annual RMD requirements even though the original beneficiary was not.

The IRS has unfortunately made the rules very complex for beneficiaries of an Inherited IRA account, so I would strongly recommend consulting with a professional to make sure you fully understand the rules.

General Rules Successor IRA Rules

If you are a successor beneficiary:

If the owner on the inherited IRA was subject to the stretch rule, you as the successor beneficiary are now subject to the 10-year rule

If the owner of the Inherited IRA was subject to the 10-year rule, you have whatever time is remaining within that original 10 year window to deplete the account balance.

Whether or not you have to take an RMD in the year they pass and in future years, is more complex, seek help from a professional.

About Michael……...

Hi, I’m Michael Ruger. I’m the managing partner of Greenbush Financial Group and the creator of the nationally recognized Money Smart Board blog . I created the blog because there are a lot of events in life that require important financial decisions. The goal is to help our readers avoid big financial missteps, discover financial solutions that they were not aware of, and to optimize their financial future.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

What happens when a beneficiary of an inherited IRA passes away?

When the original beneficiary of an inherited IRA dies, the account passes to a successor beneficiary. The successor inherits both the account and the distribution rules that applied to the original beneficiary, meaning the timing and requirements for withdrawals depend on how the first beneficiary inherited the IRA.

Do successor beneficiaries get a new 10-year window to deplete the inherited IRA?

No. If the original beneficiary was subject to the 10-year rule, the successor beneficiary only has the remaining time left in that original 10-year period to fully deplete the account. The clock does not reset when the account passes to a new beneficiary.

What if the original beneficiary was following the stretch rule?