Attention Non-Spouse 10-Year Beneficiaries: 2030 Is Rapidly Approaching

If you inherited an IRA or other retirement account from a non-spouse after December 31, 2019, the SECURE Act’s 10-year rule may create a major tax event in 2030. Many beneficiaries don’t realize how much the account can grow during the 10-year window—potentially forcing large taxable withdrawals if they wait until the final year. In this article, we explain how the 10-year rule works, why 2030 is a high-risk tax year, and planning strategies that can reduce the tax hit long before the deadline arrives.

By Michael Ruger, CFP®

Partner and Chief Investment Officer at Greenbush Financial Group

If you inherited an IRA or other retirement account from a non-spouse after December 31, 2019, the clock is ticking—and for many families, the tax consequences are coming into sharper focus.

The SECURE Act, which went into effect in 2020, dramatically changed how non-spouse beneficiaries must handle inherited retirement accounts. While these rules may have seemed far off at the time, 2030 is now just around the corner for those who inherited accounts in the first year of the new law.

In this article, we’ll cover:

How the SECURE Act’s 10-year rule works

Why 2030 could trigger significant tax liabilities

How market growth has quietly made the problem bigger

Practical tax-planning strategies to consider now

Why waiting until the last year can be costly

A Quick Refresher: What Changed Under the SECURE Act?

Prior to 2020, most non-spouse beneficiaries could “stretch” distributions from an inherited IRA over their lifetime. This allowed smaller required distributions and, in many cases, never required the account to be fully depleted.

That all changed with the SECURE Act.

For most non-spouse beneficiaries:

The inherited retirement account must be fully depleted within 10 years

The rule applies to anyone who passed away after December 31, 2019

All pre-tax dollars distributed during that period are taxable income

From the IRS’s perspective, this rule change was a revenue raiser—it ensures that inherited retirement assets become taxable within a defined window.

Why 2030 Is Such a Big Deal

For individuals who inherited a retirement account from someone who passed away in 2020, the 10-year clock runs out at the end of 2030.

That means:

Only five tax years remain (2026–2030) before the final distribution year

Any remaining balance must be distributed—and taxed—by the end of year 10

Large balances could result in substantial one-year tax spikes

Many beneficiaries have only been taking small distributions or the minimum required amounts. While that may have felt prudent at the time, it can create a tax bombshell in the final year if the account balance is still large.

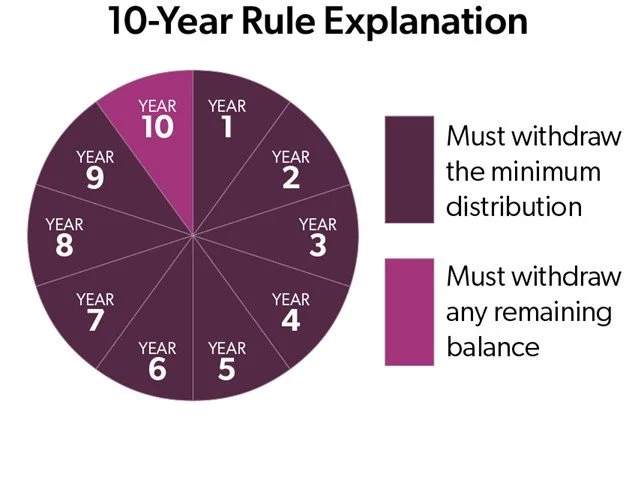

RMD Rules Add Another Layer of Complexity

Required Minimum Distribution (RMD) rules under the SECURE Act depend on whether the original account owner was already taking RMDs when they passed away.

Some beneficiaries were required to take annual RMDs

Others were not required to take annual distributions—but still must empty the account by year 10

Regardless of which category you fall into, the key issue remains the same:

Waiting too long often concentrates taxable income into fewer years.

Market Growth Has Made the Problem Bigger

Ironically, strong market performance over the past several years has amplified the issue.

For individual that have a large allocation to stocks within their inherited IRA, since the market returns have been so strong over the past few years, they may have seen the balance in their inherited IRA increase despite taking RMDs from the account each year.

This is great from a wealth-building perspective, but it also means:

Larger balances remain late in the 10-year window

Larger forced distributions

Larger tax bills await

In short, investment success can unintentionally worsen the tax outcome if distributions aren’t coordinated with a broader tax plan.

Why Smoothing Income Often Makes Sense

For many non-spouse beneficiaries, the goal should be tax smoothing—intentionally spreading distributions over the remaining years to avoid one massive taxable event in year 10.

This often means:

Taking more than the minimum each year

Coordinating distributions with your current income level

Evaluating how many years remain in your 10-year window

The sooner this planning happens, the more flexibility you typically have.

One Common Strategy: Offset Taxes With 401(K) Contributions

One tax-planning strategy we often explore with clients involves maximizing employer-sponsored retirement plan contributions.

Here’s a simplified example:

A 50-year-old employee is contributing $15,000 to their 401(k)

In 2026, they may be eligible to contribute up to $32,500

That’s an additional $17,500 of potential pre-tax deferrals

A possible strategy:

Take a $17,500 distribution from the inherited IRA (taxable)

Increase payroll deferrals so more income flows into the 401(k) pre-tax

Use the inherited IRA distribution to supplement take-home pay

Result:

Taxable income from the inherited IRA distribution is fully offset by pre-tax retirement contributions, while also shifting assets into the inherited IRA owner's personal 401(k) account, which does not have a 10-year distribution restriction.

A Critical Caveat for 2026

High-income earners should be aware that starting in 2026, certain catch-up contributions for those over age 50 may be required to be made as Roth contributions. Roth deferrals do not provide an immediate tax deduction, which could limit the effectiveness of this strategy.

When Waiting Can Make Sense

Not every situation calls for accelerating distributions.

For individuals who plan to retire before the 10-year period ends, delaying distributions may be intentional and strategic. Once paychecks stop:

Ordinary income may drop significantly

Larger inherited IRA distributions could fall into lower tax brackets

This can be a very effective approach—but only when planned in advance.

The Real Warning Sign to Watch For

This article isn’t about fear—it’s about awareness.

If you:

Inherited a retirement account after 2019

Have only been taking small distributions or RMDs

Haven’t mapped out the remaining years of your 10-year window

There’s a real risk that a large, avoidable tax liability is waiting at the end of the road.

Final Thoughts

The SECURE Act permanently changed the landscape for non-spouse beneficiaries, and 2030 is approaching faster than many realize. Thoughtful, proactive tax planning—especially in the final years of the 10-year period—can make a meaningful difference in outcomes.

Now is the time to:

Count the remaining years

Project future tax exposure

Coordinate investment, distribution, Medicare premium, and tax strategies

Advanced planning today can help turn a looming tax problem into a manageable—and sometimes even strategic—opportunity.

About Michael……...

Hi, I’m Michael Ruger. I’m the managing partner of Greenbush Financial Group and the creator of the nationally recognized Money Smart Board blog . I created the blog because there are a lot of events in life that require important financial decisions. The goal is to help our readers avoid big financial missteps, discover financial solutions that they were not aware of, and to optimize their financial future.

What Should I Do With My 401(k) From My Old Company?

When you leave a job, your old 401(k) doesn’t automatically follow you. You can leave it in the plan, roll it to your new employer’s 401(k), move it to an IRA, or cash it out. Each choice has different tax, investment, and planning implications.

Changing jobs often means leaving more than just your old desk behind. If you participated in your former employer’s 401(k) plan, you’re now faced with a decision: what should you do with that account?

It’s an important question—one that affects how you manage your retirement savings, your investment options, and potentially your tax situation. In this article, we’ll walk through the four main options for handling an old 401(k), along with the pros, cons, and planning considerations for each.

Option 1: Leave It Where It Is

Most employers allow former employees to leave their 401(k) accounts in the plan, provided the balance exceeds a minimum threshold (usually $7,000).

Pros

No immediate action required

Maintains investment options

Any growth in the account will continue to be tax-deferred

Cons

Potentially limited investment options compared to IRAs

Plan fees may be higher than alternatives

Harder to manage if you accumulate multiple old accounts

When It Makes Sense

If the old plan has strong investment options and low fees—or if you’re not ready to make a rollover decision—this can be a suitable temporary solution.

Option 2: Roll It Over to Your New Employer’s 401(k)

If your new employer offers a 401(k), you may be able to consolidate your old account into the new one.

Pros

Simplifies your retirement accounts

Keeps funds in a tax-advantaged account

May offer access to institutional fund pricing

Allows loans (if the new plan permits)

Cons

New plan may also have limited investment choices

Rollovers can take time and paperwork

Not all plans accept incoming rollovers

When It Makes Sense: If your new plan is well-managed and offers solid investment options and service, this can be a good way to consolidate and simplify your financial life.

Option 3: Roll It Over to an IRA

This is often the most flexible option for those who want greater control over their investments and potentially lower overall fees.

Pros

Broad range of investment choices

Can consolidate multiple old accounts into one

Often lower fees than 401(k) plans

More flexibility with withdrawal and Roth conversion strategies

Cons

Cannot take a loan from an IRA

Creditor protections may be weaker than in a 401(k), depending on your state

When It Makes Sense: If you’re comfortable managing your investments or working with a financial advisor, rolling into an IRA allows for more customization and control—especially when building a tax-efficient retirement income plan.

Option 4: Cash It Out

You always have the option to take the money and run—but doing so comes at a steep cost.

Pros

Provides immediate access to funds

Simple and final

Cons

Subject to income taxes

10% early withdrawal penalty if under age 59½

Permanently reduces your retirement savings

When It Makes Sense: Rarely. This is generally a last resort option, appropriate only in cases of financial emergency or if the balance is very small.

Additional Considerations

Check for Roth balances

Some plans allow Roth 401(k) contributions. If you have both pre-tax and Roth dollars, each portion must be rolled over correctly—to a Traditional IRA and Roth IRA respectively.

Watch for employer stock

If your 401(k) includes company stock, you may be eligible for Net Unrealized Appreciation (NUA) treatment, a tax strategy worth exploring with a professional.

Don’t miss the deadline

If you request a check and don’t complete a rollover within 60 days, it’s considered a distribution and taxed accordingly.

Final Thoughts

If you’ve left a job and have an old 401(k) sitting idle, now is the time to make a plan. Whether you leave it where it is, roll it over to your new plan or IRA, or—less ideally—cash it out, the decision should align with your long-term retirement goals, risk tolerance, and tax strategy.

In many cases, rolling the balance into an IRA offers the most flexibility, especially for those interested in managing taxes, investment choices, and future retirement withdrawals. If you're unsure which route is best, a financial advisor can help evaluate your options based on your full financial picture.

About Rob……...

Hi, I’m Rob Mangold. I’m the Chief Operating Officer at Greenbush Financial Group and a contributor to the Money Smart Board blog. We created the blog to provide strategies that will help our readers personally, professionally, and financially. Our blog is meant to be a resource. If there are questions that you need answered, please feel free to join in on the discussion or contact me directly.

Exceptions to the 10% Early Withdrawal Penalty for IRA Distributions

Taking money from your IRA before age 59½? Normally, that means a 10% penalty on top of income tax—but there are exceptions.

In this article, we break down the most common situations where the IRS waives the early withdrawal penalty on IRA distributions. From first-time home purchases and higher education to medical expenses and unemployment, we walk through what qualifies and what to watch out for.

When distributions are processed from an IRA account prior to age 59½, the IRS generally assesses a 10% early withdrawal penalty in addition to the ordinary income taxes owed on the amount of the distribution.

However, as with most aspects of the tax code, there are exceptions.

Whether you’re facing a financial emergency or considering strategic planning options, it’s essential to understand the legitimate circumstances under which the IRS waives the early withdrawal penalty. In this article, we’ll walk through the most common exceptions to the 10% penalty and provide some guidance on how to navigate them.

The Basics: Tax vs. Penalty

First, a quick clarification:

When you take a distribution from a traditional IRA, you generally owe ordinary income tax on the amount withdrawn. That’s true whether you’re 40 or 70. The 10% early withdrawal penalty is in addition to that tax and is designed to discourage people from prematurely accessing their retirement funds.

However, the IRS carves out several exceptions for situations it deems reasonable or necessary. These exceptions waive the penalty, not the income tax (unless otherwise noted).

Key Exceptions to the 10% Early Withdrawal Penalty

Here are the most common exceptions that apply to IRA distributions:

1. First-Time Home Purchase

One of the more well-known exceptions to the 10% early withdrawal penalty is for a first-time home purchase. The IRS allows you to take up to $10,000 from your traditional IRA—penalty-free—to put toward buying, building, or rebuilding your first home. If you’re married, both spouses can each take $10,000 from their respective IRAs for a combined total of $20,000.

Now, the term “first-time homebuyer” is a bit misleading. You don’t have to be a literal first-time buyer—you just have to not have owned a primary residence in the last two years. That opens the door for people re-entering the housing market after renting, relocating, or going through a divorce.

2. Qualified Higher Education Expenses

Tuition, fees, books, supplies, and required equipment for you, your spouse, children, or grandchildren all qualify. Room and board also qualify if the student is enrolled at least half-time.

Planning tip: If you're considering this, remember that using retirement funds for education can impact long-term growth. Exhaust other education savings options first.

3. Disability

If you become totally and permanently disabled, you can take distributions at any age without penalty. The burden of proof here is high—the IRS requires documentation from a physician.

4. Substantially Equal Periodic Payments (SEPP)

This is a strategy where you take consistent withdrawals based on your life expectancy. You must commit to this withdrawal strategy for at least 5 years or until you reach age 59½, whichever is longer.

Strategy note: SEPPs can be complex and restrictive. It’s a tool best used under close guidance from a financial advisor or CPA.

5. Unreimbursed Medical Expenses

If you have unreimbursed medical expenses that exceed 7.5% of your adjusted gross income (AGI), you can withdraw IRA funds penalty-free to cover that portion.

6. Health Insurance Premiums While Unemployed

If you’ve lost your job and received unemployment compensation for at least 12 consecutive weeks, you can use IRA funds to pay for health insurance premiums for yourself, your spouse, and dependents without triggering the penalty.

7. Death

If the IRA owner dies, the beneficiaries can take distributions from the inherited IRA without facing the 10% penalty, regardless of their age.

8. IRS Levy

If the IRS issues a levy directly on your IRA, you won’t face the penalty. Voluntary payments to the IRS, however, don’t qualify.

9. Qualified Birth or Adoption

You can withdraw up to $5,000 per child within one year of the birth or adoption without penalty. This is a relatively new provision under the SECURE Act and gives new parents a bit more flexibility.

Important Caveats

Roth IRAs have their own set of rules. Since contributions to a Roth are made with after-tax dollars, you can withdraw your contributions (not earnings) at any time, for any reason, without tax or penalty.

These 10% early withdrawal exceptions apply to IRAs, not necessarily to 401(k)s, which have a slightly different set of rules (though some overlap).

Final Thoughts

While these exceptions can be life-savers in times of need, early IRA withdrawals should still be a last resort for most people. The long-term cost in lost compounding and retirement security can be substantial.

That said, life doesn’t always go according to plan. Knowing your options—and using them strategically—can help you make informed, tax-efficient decisions when circumstances require flexibility.

About Michael……...

Hi, I’m Michael Ruger. I’m the managing partner of Greenbush Financial Group and the creator of the nationally recognized Money Smart Board blog . I created the blog because there are a lot of events in life that require important financial decisions. The goal is to help our readers avoid big financial missteps, discover financial solutions that they were not aware of, and to optimize their financial future.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

What is the 10% early withdrawal penalty on IRA distributions?

If you withdraw money from a traditional IRA before age 59½, the IRS typically charges a 10% penalty in addition to ordinary income taxes owed on the amount withdrawn.

Are there exceptions to the 10% penalty?

Yes. The IRS waives the early withdrawal penalty for specific circumstances such as:

First-time home purchase (up to $10,000)

Qualified higher education expenses

Total and permanent disability

Unreimbursed medical expenses exceeding 7.5% of AGI

Health insurance premiums while unemployed

Can I use IRA funds for a first-time home purchase without penalty?

Yes. You can withdraw up to $10,000 ($20,000 for couples) penalty-free to buy, build, or rebuild a first home. You qualify as a “first-time buyer” if you haven’t owned a primary residence in the past two years.

Are college costs or medical expenses penalty-free?

Yes. You can withdraw IRA funds penalty-free for qualified education costs for yourself, your spouse, children, or grandchildren. You can also avoid the penalty if you use funds to pay unreimbursed medical bills that exceed 7.5% of your AGI.

Do these exceptions eliminate income taxes too?

No. The 10% penalty may be waived, but standard income tax on traditional IRA withdrawals still applies unless it’s a Roth IRA contribution being withdrawn.

401(k) Catch-Up Contribution FAQs: Your Top Questions Answered (2025 Rules)

Got questions about 401(k) catch-up contributions? You’re not alone. With updated 2025 limits and new Roth rules on the horizon, this article answers the most common questions about who qualifies, how much you can contribute, and what strategic moves to consider in your 50s and early 60s.

As retirement gets closer, many individuals start to wonder how they can supercharge their savings and make up for lost time. For those age 50 and older, catch-up contributions offer a powerful opportunity to contribute more to retirement accounts beyond the standard annual limits. Below, I’ve addressed some of the most common questions I get from clients about catch-up contributions, especially with the updated 2025 rules in play.

Can I make catch-up contributions if I’m working part-time in retirement?

Yes, as long as you have earned income from a job, and you have met the plan’s eligibility requirements. So, even if you’ve scaled back your hours or semi-retired, you may still be eligible to make additional contributions.

For example, if you're age 65 and working part-time and eligible for your company’s 401(k) plan, you can contribute up to $23,500, plus an extra $7,500 in catch-up contributions for a total of $31,000 in 2025, assuming you have at least $31,000 in W2 compensation.

If you have less than $31,000 in W2 comp, you will be capped by the lesser of the annual contribution limit or 100% of your W2 compensation.

Are Roth catch-up contributions allowed?

Yes. If your employer plan offers a Roth option, you can choose to make your catch-up contributions as Roth dollars. This means you contribute after-tax money now and take qualified distributions tax-free in retirement.

This option is popular for individuals who are in the same tax bracket now as they plan to be in retirement. The Roth source also avoids required minimum distributions (RMDs) starting at age 73 or 75.

How do catch-up contributions impact required minimum distributions (RMDs)?

Catch-up contributions themselves don’t change the timing or calculation of RMDs. However, where you put the catch-up dollars can affect your future RMDs. If you contribute catch-up dollars to a Roth 401(k) and then roll over the balance to a Roth IRA prior to the RMD start age, RMDs are not required.

Adding more to the pre-tax employee deferral source within the plan may increase your future RMD requirement since pre-tax retirement accounts are subject to the annual RMD requirement once you reach age 73 (for those born 1951–1959) or 75 (for those born 1960 or later).

Should I prioritize catch-up contributions or pay down my mortgage?

This depends on your interest rate, your retirement timeline, tax bracket, and your overall financial goals. Generally, if your mortgage interest rate is below 4% and you’re behind on retirement savings, catch-up contributions may be a better use of your idle cash, especially if your investments are growing tax-deferred (pre-tax) or tax-free (roth).

However, if you’re already on track for retirement and the psychological benefit of being debt-free is important to you, putting extra cash toward your mortgage can make sense. It’s all about balancing the right financial decision with your personal preferences.

What happens if I forget to update my payroll deferrals after turning 50?

Unfortunately, you won’t automatically get the benefit since your employer’s payroll system won’t adjust your contributions just because you had a birthday. You need to take action and manually increase your deferrals to take advantage of the higher limits.

For example, if you turn 50 this year and forget to bump your 401(k) deferrals, you may miss out on contributing an additional $7,500. Worse yet, once the calendar year closes, you can't go back and make up for it.

Are there additional tax benefits associated with making catch-up contributions?

It’s common that the years leading up to retirement are often the highest income years for an individual. The additional pre-tax contributions associated with the catch-up contribution allow employees to take more of their income off the table during the peak income years and shift it into the retirement years, when ideally they are in a lower tax bracket.

What is the new age 60 – 63 catch-up contribution?

Starting in 2025, there is a new enhanced catch-up contribution available to employees covered by 401(k) and 403(b) plans who are aged 60 to 63. Instead of being limited to just the regular $7,500 catch-up contribution, in 2025, employees age 60 – 63 will be allowed to make a catch-up contribution equal to $11,250.

What is the Mandatory Roth catch-up for high income earners?

Starting in 2026, and for the following years, if an employee makes more than $145,000 in W2 compensation (indexed for inflation) with the same employer in the previous year, that employee will no longer be allowed to make pre-tax catch-up contributions. If they make a catch-up contribution, it will be required to be a Roth catch-up contribution.

Final Thoughts…

Whether you’re still decades from retirement or just a few years away, catch-up contributions are a crucial part of retirement planning for those age 50 and older. With the 2025 limits now in place and Roth rules continuing to evolve, understanding how these contributions fit into your broader plan can help you save smarter — and avoid costly mistakes.

About Michael……...

Hi, I’m Michael Ruger. I’m the managing partner of Greenbush Financial Group and the creator of the nationally recognized Money Smart Board blog . I created the blog because there are a lot of events in life that require important financial decisions. The goal is to help our readers avoid big financial missteps, discover financial solutions that they were not aware of, and to optimize their financial future.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

What are catch-up contributions and who qualifies for them?

Catch-up contributions allow individuals age 50 and older to contribute additional funds to retirement accounts beyond the standard annual limits. For 2025, employees can contribute up to $23,500 to a 401(k) plus an extra $7,500 in catch-up contributions, for a total of $31,000 — provided they have sufficient earned income.

Can part-time workers make catch-up contributions?

Yes. As long as you have earned income and meet your employer plan’s eligibility requirements, you can make catch-up contributions even if you’re working part-time. The total contribution amount cannot exceed 100% of your W-2 compensation.

Are Roth catch-up contributions available?

If your employer plan offers a Roth option, you can make your catch-up contributions as Roth dollars. Roth contributions are made after tax, grow tax-free, and qualified withdrawals are also tax-free, offering flexibility for future tax planning.

How do catch-up contributions affect required minimum distributions (RMDs)?

Catch-up contributions do not change when RMDs begin, but the type of account matters. Pre-tax catch-up dollars increase your future RMDs, while Roth 401(k) contributions can be rolled into a Roth IRA before RMD age to avoid mandatory withdrawals altogether.

Should I prioritize catch-up contributions or pay down my mortgage?

It depends on your financial situation. If your mortgage rate is low (under 4%) and you’re behind on retirement savings, maximizing catch-up contributions may be beneficial. However, paying down your mortgage may make sense if you’re already on track for retirement and value being debt-free or if you have a higher interest rate on your mortgage.

What happens if I forget to increase my deferrals after turning 50?

Your employer’s payroll system won’t automatically adjust contributions, so you must update them manually. Missing the adjustment means forfeiting that year’s extra contribution opportunity — once the year ends, you can’t retroactively make up the difference.

What is the new enhanced age 60–63 catch-up contribution for 2025?

Starting in 2025, employees aged 60 to 63 can make a larger catch-up contribution of up to $11,250 to 401(k) and 403(b) plans, providing an additional savings boost in the final years before retirement.

What is the new rule for high-income earners and Roth catch-ups?

Beginning in 2026, employees earning more than $145,000 (indexed for inflation) in W-2 income with the same employer will be required to make catch-up contributions as Roth contributions — pre-tax catch-ups will no longer be allowed for this group.

401(k) Catch-Up Contributions Explained: Maximize Your Retirement Savings in 2025

Turning 50? It’s time to boost your retirement savings.

This article breaks down the updated 2025 401(k) catch-up contribution limits, new rules for ages 60–63, and whether pre-tax or Roth contributions make the most sense for your situation.

For individuals aged 50 or older, catch-up contributions allow for additional retirement savings during what are often their highest earning years. With updated limits and new provisions taking effect in 2025, this strategy can be especially valuable for those looking to strengthen their financial position ahead of retirement and maximize tax efficiency in what are typically their highest income years leading up to retirement.

Below, I break down the 2025 catch-up contribution limits, rules, and strategic considerations to help you make informed decisions.

What Are Catch-Up Contributions?

Catch-up contributions allow individuals aged 50 or older to contribute above the standard annual limits to retirement accounts. You’re eligible to make catch-up contributions starting in the calendar year you turn 50.

2025 Contribution Limits

Here are the updated 2025 401(k) contribution limits for each plan type:

401(k), 403(b), 457(b):

Standard limit: $23,500

Age 50 – 59 & Age 64+ catch-up: $7,500

Age 60 – 63 catch-up: $11,250

New 401(k) Age 60–63 Catch-Up Limits

Beginning in 2025, a new tier of higher catch-up limits will apply to individuals between ages 60 and 63. Under the SECURE 2.0 Act, these individuals can contribute an additional amount equal to 50% of the regular catch-up contribution for that plan year. For 2025, this equates to an extra $3,750, bringing the total possible contribution to $34,750 for 401(k), 403(b), and 457(b) plans. This enhanced catch-up contribution is optional for employers, so it's important to confirm with your plan sponsor whether this provision is available in your plan.

To learn more, read our article: New Age 60 – 63 401(k) Enhanced Catch-up Contribution Starting in 2025

Pre-Tax vs. Roth Catch-Up Contributions

Employer-sponsored retirement plans often allow participants to choose whether their catch-up contributions are made on a pre-tax or Roth (after-tax) basis. The best approach depends on income levels, expected tax rates in retirement, and broader financial planning goals.

Pre-tax contributions reduce your taxable income today but are taxed when withdrawn in retirement.

Roth contributions provide no current tax deduction but grow and distribute tax-free in retirement.

When Pre-Tax May Make Sense:

You're in a high tax bracket today (e.g., 24%+)

You expect to be a lower tax bracket during the retirement years

Example:

Tom is age 60, married, and earns $400,000 annually, placing him in the 32% federal tax bracket. In the next 5 years, Tom expects to retire and be in a lower federal tax bracket. By making pre-tax catch-up contributions now, it will allow him to reduce his current taxable income, while potentially taking distributions in a lower tax bracket later.

When Roth May Make Sense:

You expect your current tax rate to be roughly the same in retirement

You already have substantial pre-tax retirement account balances

You expect tax rates to rising in the future

Example:

Susan is age 52, single filer, earns $125,000 per year, and is in the 22% tax bracket. She expects her income to remain steady over time. By choosing Roth catch-up contributions, she pays tax now at a relatively low rate and avoids taxation on future withdrawals.

Mandatory Roth Catch-Up Contributions for High Earners (Effective 2026)

Starting in 2026, individuals earning $145,000 or more (adjusted for inflation) in wages from the same employer in the previous year will be required to make catch-up contributions to their workplace plan on a Roth basis. This rule applies only to employer-sponsored plans (like 401(k)s) and does not impact Simple IRA plans. For 2025, these Roth rules have been delayed, giving high-income earners time to prepare.

To learn about the rules and exceptions for high earners, read our article: Mandatory 401(k) Roth Catch-up Details Confirmed by IRS January 2025

The Big Picture: Why This Strategy Matters Near Retirement

For individuals within five to ten years of retirement, catch-up contributions provide an opportunity to meaningfully increase retirement savings without relying on higher investment returns or making dramatic lifestyle changes. The added contributions also support strategic tax planning by allowing savers to choose between pre-tax and Roth treatment based on their broader income picture.

Catch-up contributions can help:

Maximize tax-advantaged savings when your income is typically at its highest

Take advantage of compound growth on a larger balance

Strategically shift assets into Roth accounts for future tax-free income

Consider the numbers:

A 60-year-old contributing the full $34,750 annual catch-up amount for three consecutive years could accumulate over $111,000 in additional retirement savings, assuming a 7% annual return. If contributed to a Roth 401(k), those funds would grow and be distributed tax-free, offering valuable flexibility in retirement.

Even if retirement is only a few years away, catch-up contributions can play a significant role in improving retirement readiness and reducing future tax burdens.

About Michael……...

Hi, I’m Michael Ruger. I’m the managing partner of Greenbush Financial Group and the creator of the nationally recognized Money Smart Board blog . I created the blog because there are a lot of events in life that require important financial decisions. The goal is to help our readers avoid big financial missteps, discover financial solutions that they were not aware of, and to optimize their financial future.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

What are catch-up contributions and who qualifies for them?

Catch-up contributions allow individuals aged 50 or older to contribute more to retirement accounts than the standard annual limit. Eligibility begins in the calendar year you turn 50, regardless of your income level or how close you are to retirement.

What are the 2025 catch-up contribution limits?

In 2025, employees can contribute up to $23,500 to a 401(k), 403(b), or 457(b) plan. Those aged 50–59 and 64 or older can contribute an additional $7,500, while individuals aged 60–63 can make an enhanced catch-up contribution of $11,250, for a total of $34,750 if allowed by their employer’s plan.

How does the new age 60–63 catch-up rule work?

Starting in 2025, individuals between ages 60 and 63 can make a higher catch-up contribution equal to 150% of the standard catch-up limit. This provision under the SECURE 2.0 Act lets older workers maximize savings during their final working years, but availability depends on whether an employer adopts the rule.

Should I make my catch-up contributions pre-tax or Roth?

The best option depends on your tax situation. Pre-tax contributions reduce taxable income now and are ideal if you expect to be in a lower tax bracket in retirement. Roth contributions are made after-tax but grow tax-free and are advantageous if you expect future tax rates to rise or your income to remain steady.

What is the mandatory Roth catch-up rule for high-income earners?

Beginning in 2026, employees earning $145,000 or more (adjusted for inflation) from the same employer in the previous year must make catch-up contributions on a Roth basis. This means contributions will be made after tax, and future withdrawals will be tax-free.

Why are catch-up contributions especially important near retirement?

Catch-up contributions help individuals nearing retirement boost savings during peak earning years without depending solely on market growth. They also provide tax planning flexibility by letting savers choose between pre-tax and Roth options based on their expected future income and tax rates.

Multi-Generational Roth Conversion Planning

With the new 10-Year Rule in effect, passing along a Traditional IRA could create a major tax burden for your beneficiaries. One strategy gaining traction among high-net-worth families and retirees is the “Next Gen Roth Conversion Strategy.” By paying tax now at lower rates, you may be able to pass on a fully tax-free Roth IRA—one that continues growing tax-free for years after the original account owner has passed away.

With the new 10-Year Rule in place for non-spouse beneficiaries of retirement accounts, one of the new tax strategies for passing tax-free wealth to the next generation is something called the “Next Gen Roth Conversion Strategy”. This tax strategy works extremely well when the beneficiaries of the retirement account are expected to be in the same or higher tax bracket than the current owner of the retirement account.

Here's how the strategy works. The current owner of the retirement account begins to initiate large Roth conversions over the course of a number of years to purposefully have those pre-tax retirement dollars taxed in a low to medium tax bracket. This way, when it comes time to pass assets to their beneficiaries, the beneficiaries inherit Roth IRA assets instead of pre-tax Traditional IRA and 401(k) assets that could be taxed at a much higher rate due to the requirement to fully liquidate and pay tax on those assets within a 10-year period.

In addition to lowering the total income tax paid on those pre-tax retirement assets, this strategy can also create multi-generational tax-free wealth, reduce the size of an estate to save on estate taxes, and reduce future RMDs for the current account owner.

10-Year Rule for Non-Spouse Beneficiaries

This tax strategy surfaced when the new 10-Year Rule went into place with the passing of the Secure Act. Non-spouse beneficiaries who inherit pre-tax retirement accounts are now required to fully deplete and pay tax on those account balances within a 10-year period following the passing of the original account owner. In many cases when children inherit pre-tax retirement accounts from their parents, they are still working, which means that they already have income on the table.

For example, if Josh, a non-spouse beneficiary, inherits a $600,000 Traditional IRA from his father when he is age 50, he would be required to pay tax on the full $600,000 within 10 years of his father passing. But what if Josh is married and he and his wife still work and are making $360,000 per year? If Josh and his wife do not plan to retire within the next 10 years, the $600,000 that is required to be distributed from that inherited IRA while they are still working could be subject to very high tax rates since the taxable distribution stacks on top of the $360,000 that they are already making. A large portion of those IRA distributions could be subject to the 32% federal tax bracket.

If Josh’s father had started making $100,000 Roth conversions each year while both he and Josh’s mother were still alive, they could have taken advantage of the 22% Federal Tax Bracket I in 2025 (which ranges from $96,951 to $206,000 in taxable income). If they had very little other income in retirement, they could have processed large Roth conversions, paid just 22% in federal taxes on the converted amount, and eventually passed a Roth IRA on to Josh. Utilizing this strategy, the full $600,000 pre-tax IRA would have been subject to the parent’s federal tax rate of 22% as opposed to Josh’s tax rate of 32%, saving approximately $60,000 in taxes paid to the IRS.

Tax Free Accumulations For 10 More Years

But it gets better. By Josh’s parents processing Roth conversions while they were still alive, not only is there multigenerational tax savings, but when John inherits a Roth IRA instead of a Traditional IRA from his parents, all of the accumulation within that Roth IRA since the parents completed the conversion, PLUS 10 years after Josh inherits the Roth IRA, are completely tax-free.

Multi-generational Tax-Free Wealth

If you are a non-spouse beneficiary, whether you inherited a pre-tax retirement account or a Roth IRA, you are subject to the 10-year distribution rule (unless you qualify for one of the exceptions). With a pre-tax IRA or 401(k), not only is the beneficiary required to deplete and pay tax on the account within 10 years, but they may also be required to process RMDs (required minimum distributions) from their inherited IRA each year, depending on the age of the decedent when they passed away.

With an Inherited Roth IRA, the account must be depleted in 10 years, but there is no annual RMD requirement, because RMDs do not apply to Roth IRAs subject to the 10-year rule. So, essentially, someone could inherit a $500,000 Roth IRA, take no money out for 9 years, and then at the end of the 10th year, distribute the full balance TAX-FREE. If the owner of the inherited Roth IRA invests the account wisely and obtains an 8% annualized rate of return, at the end of year 10 the account would be worth $1,079,462, which would be withdrawn completely tax-free.

Reduce The Size of an Estate

For individuals who are expected to have an estate large enough to trigger estate tax at the federal and/or state level, this “Next Gen Roth Conversion” strategy can also help to reduce the size of the estate subject to estate tax. When a Roth conversion is processed, it’s a taxable event, and any tax paid by the account owner essentially shrinks the size of the estate subject to taxation.

If someone has a $15 million estate, and included in that estate is a $5 million balance in a Traditional IRA and that person does nothing, it creates two problems. First, the balance in the Traditional IRA will continue to grow, increasing the estate tax liability that will be due when the individual passes assets to the next generation. Second, if there are only two beneficiaries of the estate, each beneficiary will have to move $2.5 million into their own inherited IRA and fully deplete and pay tax on that $2.5M PLUS earnings within a 10-year period. Not great.

If, instead, that individual begins processing Roth conversions of $500,000 per year, and over a course of 10 years can fully convert the Traditional IRA to a Roth IRA (ignoring earnings), two good things can happen. First, if that individual pays an effective tax rate of 30% on the conversions, it will decrease the size of the estate by $1.5 million ($5M x 30%), potentially lowering the estate tax liability when assets are passed to the beneficiaries of the estate. Second, even though the beneficiaries of the estate would inherit a $3.5M Roth IRA instead of a $5M Traditional IRA, no RMDs would be required each year, the beneficiaries could invest the Inherited Roth IRA which could potentially double the value of the Inherited Roth IRA during that 10-year period, and withdraw the full balance at the end of year 10, completely tax free, resulting in big multi-generational tax free wealth.

The Power of Tax-Free Compounding

Not only does the beneficiary of the Roth IRA benefit from tax-free growth for the 10 years following the account owner's death, but they also receive the benefit of tax-free growth and withdrawal within the Roth IRA, as long as the account owner is still alive. For example, if someone begins these Roth conversions at age 70 and they live until age 90, that’s 20 years of compounding, PLUS another 10 years after they pass away, so 30 years in total.

A quick example showing the power of this tax-free compounding effect: someone processes a $200,000 Roth conversion at age 70, lives until age 90, and achieves an 8% per year rate of return. When they pass away at age 90, the balance in their Roth IRA would be $932,191. The non-spouse beneficiary then inherits the Roth IRA and invests the account, also achieving an 8% annual rate of return. In year 10, the Inherited Roth IRA would have a balance of $2,012,531. So, the original owner of the Traditional IRA paid tax on $200,000 when the Roth conversion took place, but it created a potential $2M tax-free asset for the beneficiaries of that Roth IRA.

Reduce Future RMDs of Roth IRA Account Owner

Outside of creating the multi-generational tax-free wealth, by processing Roth conversions in retirement, it’s shifting money from pre-tax retirement accounts subject to annual RMDs into a Roth IRA that does not require RMDs. First, this lowers the amount of future taxable RMDs to the Roth IRA account owner because assets are being shifted from their Traditional IRA to Roth IRA, and second, since RMDs are not required from Roth IRAs, the assets in that IRA are allowed to continue to compound investment returns without disruption.

About Michael……...

Hi, I’m Michael Ruger. I’m the managing partner of Greenbush Financial Group and the creator of the nationally recognized Money Smart Board blog . I created the blog because there are a lot of events in life that require important financial decisions. The goal is to help our readers avoid big financial missteps, discover financial solutions that they were not aware of, and to optimize their financial future.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

What is the “Next Gen Roth Conversion Strategy”?

The Next Gen Roth Conversion Strategy involves gradually converting pre-tax retirement assets, such as Traditional IRAs or 401(k)s, into Roth IRAs while the account owner is in a lower tax bracket. This allows heirs to inherit Roth assets that grow and distribute tax-free rather than being forced to pay higher taxes under the 10-Year Rule for inherited pre-tax accounts.

How does the 10-Year Rule affect inherited retirement accounts?

Under the SECURE Act, non-spouse beneficiaries must fully deplete inherited pre-tax retirement accounts within 10 years of the original owner’s death. This often forces distributions during high-income years, which can push beneficiaries into higher tax brackets and increase total taxes owed.

Why is this strategy beneficial for high-earning heirs?

When heirs are in the same or higher tax bracket as the original account owner, converting to a Roth during the parent’s lifetime allows the taxes to be paid at a lower rate. The heirs then inherit a Roth IRA that continues to grow tax-free and can be withdrawn without triggering additional income tax.

How does the strategy create multi-generational tax-free wealth?

After the account owner passes, heirs can keep the inherited Roth IRA invested for up to 10 years without required minimum distributions (RMDs). All investment growth during that time is tax-free, and the full balance can be withdrawn at the end of year 10 with no taxes owed.

Can Roth conversions also reduce estate taxes?

Yes. The taxes paid during the conversion process reduce the overall size of the estate, which may lower exposure to federal or state estate taxes. Converting pre-tax assets to Roth IRAs can therefore benefit both the heirs and the estate itself.

How does this strategy help minimize future RMDs?

By converting pre-tax accounts to Roth IRAs, retirees reduce the balance of assets subject to required minimum distributions. Since Roth IRAs do not require RMDs during the owner’s lifetime, more assets can continue compounding tax-free for longer.

What makes the Next Gen Roth Conversion Strategy so powerful?

It combines proactive tax planning, estate reduction, and multi-generational wealth transfer. Taxes are paid strategically at lower rates, future RMDs are minimized, and beneficiaries receive assets that can grow for up to a decade after inheritance—completely tax-free.

Inherited IRA $20,000 State Tax Exemption for New York Beneficiaries Under Age 59 ½

Have you or someone you know recently inherited an IRA in New York? There’s a tax-saving opportunity that many beneficiaries overlook, and we’re here to help you take full advantage of it.

Did you know that if the decedent was 59 ½ or older, you might qualify for a $20,000 New York State income tax exemption on distributions from the inherited IRA—even if you’re under age 59 ½? This little-known benefit could save you a significant amount on taxes, but navigating the rules can be tricky.

Topics covered:

🔹 The $20,000 annual NY State tax exemption for inherited IRAs

🔹 Rules for New York beneficiaries under age 59 ½

🔹 How this exemption can impact the 10-Year Rule distribution strategy

🔹 How tax exemptions are split between multiple beneficiaries

🔹 What if one of the beneficiaries is located outside of NY?

For individuals who inherit a retirement account in New York state, there is a little-known tax law that allows an owner of an inherited IRA to distribute up to $20,000 from their inherited IRA EACH YEAR without having to pay New York State income tax on those distributions. While this $20,000 state tax exemption typically only applies to individuals age 59 ½ or older, there is a special rule that allows beneficiaries of retirement accounts to “inherit” the $20,000 tax exemption from the decedent and avoid having to pay state tax on the distributions from their Inherited IRA, even though they themselves are under the age of 59 ½.

Inherited IRA Owners Under Age 59½

If you inherit a retirement account and you are under the age of 59 ½, there is a whole host of rules that you have to follow in regard to the new 10-Year Distribution Rule, required minimum distributions, and beneficiaries grandfathered in under the old “stretch rules.” We have a separate article that covers these topics in detail:

GFG Article on Inherited IRA Rules for Non-spouse Beneficiaries

However, for the purposes of this article, we are just going to focus on the taxation of distributions from inherited IRAs, specifically the tax exemption for residents of New York State.

Universal Tax Rules at the Federal Level

Regardless of what state you live in, there are tax laws at the federal level that apply to all owners of inherited IRA accounts. The two main rules are:

For inherited IRA owners that are under the age of 59 ½, the 10% early withdrawal penalty does not apply to distributions taken from an inherited IRA.

All distributions from inherited IRA accounts are subject to taxation at the federal level.

IRA Taxation Rules Vary State by State

While the federal taxation rules are the same for everyone, the state rules for the taxation of inherited IRAs vary from state to state. In this article, we will be focusing on the inherited IRA tax rules for residents of New York State.

New York State IRA Taxation

New York has a special rule that once an individual reaches age 59 ½ they are allowed to take distributions from pre-tax retirement account sources and not pay NYS Income tax on the first $20,000 each year. This includes distributions from any type of pre-tax IRA, 401(k), private pension plans, or other types of pre-tax employer-sponsored retirement plans.

But……..New York has another special rule that allows a beneficiary of a retirement account to INHERIT the decedent’s $20,000 state income tax exemption and use it when they take distributions from the inherited IRA account, even though the beneficiary may be under the age of 59 ½.

Rule 1: Decedent Must Have Reached Age 59 ½

For the beneficiary to “inherit” the decedent’s $20,000 NYS IRA tax exemption, the decent must have reached age 59 ½ before they passed away. If the decedent passed away prior to age 59 ½, the beneficiaries of the retirement account are not eligible to inherit the $20,000 NYS tax exemption.

Rule 2: The Beneficiary Must Be A Resident of New York

In order to qualify for the $20,000 NYS tax exemption on the distributions from the inherited IRA account, the beneficiary must be a resident of New York State, which makes sense because if the beneficiary was not a resident of New York, they would not be filing a NY tax return.

Rule 3: The $20,000 NYS Exemption with Multiple Beneficiaries

It’s not uncommon for someone to have more than one beneficiary assigned to their retirement accounts. For purposes of the allocation of the NYS $20,000 exemption, the $20,000 annual exemption is split evenly between the beneficiaries of their retirement accounts. For example, if Sue passed away at age 62 and her 2 children Tracy and Mia, both New York Residents, are listed as 50%/50% beneficiaries, once the assets have been moved into the inherited IRAs for Tracy and Mia, they would both be eligible to claim a $10,000 state tax exemption each year for any distributions taken from the Inherited IRA even though Tracy & Mia are both under that age of 59 ½.

Rule 4: What If One of the Beneficiaries Lives Outside of New York?

But what happens if not all of the beneficiaries are New York residents? Does the beneficiary that lives in New York get to keep the full $20,000 New York State tax exemption?

Answer: No. In cases where one beneficiary is a NY resident and there are other beneficiaries that live outside of New York State, the $20,000 New York State tax exemption is still split evenly among the number of beneficiaries even though there is no tax benefit for the beneficiaries that are domiciled outside of New York.

Follow Up Question: Is there any way for the beneficiaries outside of New York to assign their portion of the $20,000 NYS IRA tax exemption to the beneficiary that lives in New York? Answer: No.

Rule 5: Multiple Retirement Accounts with Different Beneficiaries

So what happens if Tim is age 35, and is the 100% beneficiary of his father’s Traditional IRA, but his father also had a 401(k) account with Tim and his 3 siblings listed as beneficiaries? Does Tim get the full $20,000 NYS exemption for distribution from his Inherited IRA that came from the IRA that he was the sole beneficiary of?

Answer: No. Technically, the $20,000 exemption is split evenly among all of the beneficiaries of the decedent’s retirement accounts in aggregate. In the example above, since Tim was one of four beneficiaries on his father’s 401(k), he would be allocated $5,000 (25%) of the $20,000 New York State exemption each year.

Rule 6: How Would You Find Out “IF” There Are Other Beneficiaries?

There are cases where someone will get notified that they are a beneficiary of a retirement account without knowing who the other beneficiaries are on that account. Most custodians will not disclose who the other beneficiaries are, they typically just notify you of the share of the retirement account that you are entitled to. In this case, how do you know how to split up the $20,000 NYS exemption?

Answer: That is an excellent question. I have no idea.

Rule 7: The $20,000 exemption is an ANNUAL Exemption

The $20,000 NYS tax exemption for distributions from inherited IRAs is an ANNUAL exemption, meaning the owners of the inherited IRAs can use this exemption each year. For example, Ryan’s father passed away at age 70, Ryan is only age 45, he was the sole beneficiary of his father’s Traditional IRA account, Ryan would be allowed to distribute $20,000 per year for his Inherited IRA account and he would avoid having to pay New York State income tax on those distributions up to $20,000 each year.

Tax Note: Once the annual distributions exceed $20,000, NYS income tax will apply.

Rule 8: Beneficiary Already Age 59 ½ or Older

If a non-spouse beneficiary is a New York resident and already age 59 ½ or older, do they get to claim both their own $20,000 NYS tax exemption on distributions from their personal pre-tax retirement accounts and then another $20,000 exemption from the inherited accounts?

Answer: No. The $20,000 NYS tax exemption has an aggregate limit for all pre-tax retirement accounts in a given tax year.

Rule 9: State Pensions PLUS $20,000 NYS Exemption

New York also has the favorable rule that if you are receiving a NYS pension, the amount received from the state pension does not count towards the $20,000 annual IRA tax exemption rule. For example, you could have someone who retired from NYS at age 55 is receiving a NYS pension for $40,000 per year, and if they inherited an IRA, they may also be able to exclude the first $20,000 distributed from the IRA from NYS income taxation.

Tax Strategies For Non-Spouse Beneficiaries Subject to 10-Year Rule

Now that many non-spouse beneficiaries are subject to the new Secure Act 10-Year Rule, requiring them to deplete the inherited IRA within 10 years, if the decedent was over the age of 59 ½ when they passed, it’s important to proactively plan the distribution schedule to take full advantage of the $20,000 NYS tax exemption otherwise owners of the inherited IRA could end up paying more taxes to New York State that could have been avoided.

About Michael……...

Hi, I’m Michael Ruger. I’m the managing partner of Greenbush Financial Group and the creator of the nationally recognized Money Smart Board blog . I created the blog because there are a lot of events in life that require important financial decisions. The goal is to help our readers avoid big financial missteps, discover financial solutions that they were not aware of, and to optimize their financial future.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

What is the New York State $20,000 exemption for inherited IRAs?

New York allows beneficiaries of inherited retirement accounts to exclude up to $20,000 per year in distributions from New York State income tax. This rule typically applies to individuals age 59½ or older, but beneficiaries can “inherit” this exemption from the decedent even if they are under 59½.

Who qualifies for the $20,000 New York State exemption on inherited IRAs?

To qualify, the decedent must have been at least age 59½ at the time of death, and the beneficiary must be a current resident of New York State. If both conditions are met, the beneficiary can exclude up to $20,000 in distributions per year from state income tax.

Does the decedent’s age matter for the exemption?

Yes. The decedent must have reached age 59½ before passing away for the beneficiary to inherit the $20,000 exemption. If the decedent died before age 59½, the exemption does not apply to the inherited IRA.

Can beneficiaries outside of New York use this exemption?

No. The beneficiary must be a New York State resident to claim the exemption. Beneficiaries living outside New York cannot use or assign their portion of the $20,000 exemption to others.

How is the $20,000 exemption divided among multiple beneficiaries?

If multiple beneficiaries inherit the decedent’s retirement accounts, the $20,000 annual exemption is split evenly among them. For example, if there are two beneficiaries, each can claim a $10,000 exemption per year; if there are four, each can claim $5,000.

What happens if only one of several beneficiaries lives in New York?

The $20,000 exemption is still split evenly among all beneficiaries, even if only one resides in New York. Nonresident beneficiaries cannot transfer their unused exemption to New York residents.

Does the exemption apply separately to each inherited account?

No. The $20,000 exemption applies in total across all inherited retirement accounts from the same decedent. It does not reset per account.

Can beneficiaries use this exemption every year?

Yes. The $20,000 exemption is an annual benefit. Beneficiaries can exclude up to $20,000 in inherited IRA distributions from New York State income tax each year until the account is depleted.

If the beneficiary is already age 59½, can they claim two exemptions?

No. A beneficiary who is already 59½ or older can only claim one $20,000 exemption per year in total across all their retirement accounts, including both personal and inherited accounts.

Does the exemption affect New York State pensions?

No. New York State pension income is already fully exempt from state income tax. The $20,000 retirement distribution exemption applies separately to IRA and 401(k) distributions, meaning eligible retirees can exclude both their NYS pension income and up to $20,000 in IRA distributions annually.

How can beneficiaries maximize the tax benefit under the 10-Year Rule?

Beneficiaries subject to the Secure Act’s 10-Year Rule should consider spreading withdrawals strategically to use the $20,000 New York exemption each year, reducing overall state taxes on inherited IRA distributions.

Tax-Loss Harvesting Rules: Short-Term vs Long-Term, 30-Day Wash Rule, $3,000 Tax Deduction, and More…….

As an investment firm, November and December is considered “tax-loss harvesting season” where we work with our clients to identify investment losses that can be used to offset capital gains that have been realized throughout the year in an effort to reduce their tax liability for the year. But there are a lot of IRS rule surrounding what “type” of realized losses can be used to offset realized gains and retail investors are often unaware of these rules which can lead to errors in their lost harvesting strategies.

As an investment firm, November and December is considered “tax-loss harvesting season”, where we work with our clients to identify investment losses that can be used to offset capital gains that have been realized throughout the year to reduce their tax liability for the year. But there are a lot of IRS rules surrounding what “type” of realized losses can be used to offset realized gains, and retail investors are often unaware of these rules which can lead to errors in their lost harvesting strategies. In this article, we will cover loss harvesting rules for:

Realized Short-term Gains

Realized Long-term Gains

Mutual Fund Capital Gains Distributions

The $3,000 Annual Realized Loss Income Deduction

Loss Carryforward Rules

Wash Sale Rules

Real Estate Investments

Business Gains or Losses

Short-Term vs Long-Term Gain and Losses

Investment gains and losses fall into two categories: Long-Term and Short-Term. Any investment, whether it’s a stock, mutual fund, or real estate, if you buy it and then sell it within 12 months, that gain or loss is classified as a “short-term” capital gain or loss and is taxed to you as ordinary income.

If you make an investment and hold it for more than 1 year before selling it, your gain or loss is classified as a “long-term” capital gain or loss. If it’s a gain, it’s taxed at the preferential long-term capital gains rates. The long-term capital gains tax rate that you pay varies based on the amount of your income for the year (including the amount of the long-term capital gain). For 2024, here is the table:

Note: For individuals in the top tax bracket, there is a 3.8% Medicare surcharge added on top of the federal 20% long-term capital gains tax rate, so the top long-term capital gains rate ends up being 23.8%. For individuals that live in states with income tax, many do not have special tax rates for long-term capital gains and they are simply taxed as additional ordinary income at the state level.

What Is Year End Loss Harvesting?

Loss harvesting is a tax strategy where investors intentionally sell investments that have lost value to generate a realized loss to offset a realized gain that they may have experienced in another investment. Example, if a client sold Nvidia stock in May 2024 and realized a long-term capital gain of $100,000 in November and they look at their investment portfolio an notice that their Plug Power stock has an unrealized loss of $100,000, if they sell the Plug Power stock and generate a $100,000 realized loss, it would completely wipes out the tax liability on the $100,000 gain that they realized on the sale of their Nvidia stock earlier in the year.

Loss harvesting is not an all or nothing strategy. In that same example above, even if that client only had $30,000 in unrealized losses in Plug Power, realizing the loss would at least offset some of the $100,000 realized gain in their Nvidia stock sale.

Long-Term Losses Only Offset Long-Term Gains

It's common for investors to have both short-term realized capital gains and long-term realized capital gains in a given tax year. It’s important for investors to understand that there are specific IRS rules as to what TYPE of investment losses offset investment gains. For example, realized long-term losses can only be used to offset realized long-term capital gains. You cannot use realized long-term losses to offset a short-term capital gain.

Short-Term Losses Can Offset Both Short-Term & Long-Term Gain

However, realized short-term losses can be used to offset EITHER short-term or long-term capital gains. If an investor has both short-term and long-term gains, the short-term realized losses are first used to offset any short-term gains, and then the remainder is used to offset the long-term gains.

Loss Carryforward

What happens when your realized loss is greater than your realized gain? You have what’s called a “loss carryforward”. If you have unused realized investment losses, those unused losses can be used to offset investment gains in future tax years. Example, Joe sells company XYZ and has a $30,000 realized long-term loss. The only other investment income that Joe has is a short-term gain of $5,000. Since you cannot use a long-term loss to offset a short-term gain, Joe’s $30,000 in realized long-term losses cannot be used in this tax year. However, that $30,000 loss will carryforward to the next tax year, and if Joe has a long-term realized gain of $40,000 that next year, he can use the $30,000 carryforward loss to offset a larger portion of that $40,000 realized gain.

When do carryforward losses expire? Answer: never (except for when you pass away). The carryforward loss will continue until you have a gain to offset it.

$3,000 Capital Loss Annual Tax Deduction

Even if you have no realized capital gains for the year, it may still make sense from a tax standpoint to generate a $3,000 realized loss from your investment accounts because the IRS allows you deduct up to $3,000 per year in capital losses against your ordinary income. Both short-term and long-term losses qualify toward that $3,000 annual tax deduction.

Example: Sarah has no realized capital gains for the year, but on December 15th she intentionally sells shares of a mutual fund to generate a $3,000 long-term realized loss. Sarah can now use that $3,000 loss to take a deduction against her ordinary income.

Tax Note: You do not need to itemize to take advantage of the $3,000 tax deduction for capital losses. You can elect to take the standard deduction when filing your taxes and still capture the $3,000 tax deduction for capital losses.

The $3,000 annual loss tax deduction can also be used to eat up carryforward losses. If we go back to our example with Joe who had the $30,000 realized long-term loss, if he does not have any future capital gains to offset them with the carryforward loss, he could continue to deduct $3,000 per year against his ordinary income over the next 10 years, until the loss has been fully deducted.

Mutual Fund Capital Gain Distribution

For investors that use mutual funds as an investment vehicle within a taxable investment account, certain mutual funds will issue a “capital gains distribution”, typically in November or December of each year, which then generates taxable income to the shareholder of that mutual fund, whether they sold any shares during the year.

When mutual funds issue capital gains distributions, it’s common that a majority of the capital gains distributions will be long-term capital gains. Similar to normal realized long-term capital gains, investors can loss harvest and generate realized losses to offset the long-term capital gains distribution from their mutual fund holdings in an effort to reduce their tax liability.

The Wash Sale Rule

When loss harvesting, investors have to be aware of the IRS “Wash Sale Rule”. The wash sale rule states that if you sell a security at a loss and the rebuy a substantially identical security within 30 days following the date of the sale, a realized loss cannot be captured by the taxpayer.

Example: Scott sells the Nike stock on December 1, 2024 which generates a $10,000 realize loss, but then Scott repurchases Nike stock on December 25, 2024. Since Scott repurchased Nike stock within 30 days of the sell day, he can no longer use the $10,000 realized loss generated by his sell transaction on December 1st due to the IRS 30 Day Wash Rule.

Also make note of the term “substantially identical” security. If you sell the Vanguard S&P 500 Index ETF to realize a loss but then purchase the Fidelity S&P 500 Index ETF 15 days later, while they are two different investments with different ticker symbols, the IRS would most likely consider them substantially identical triggering the Wash Sale rule.

Real Estate & Business Loss Harvesting

While most of the examples today have been centered around stock investments, the lost harvesting strategy can be used across various asset classes. We have had clients that have sold their business, generating a large long-term capital gain, and then we have them going into their taxable brokerage account looking for investment holdings that have unrealized losses that we can realize to offset the taxable long-term gain from the sale of their business.

The same is true for real estate investments. If a client sells a property at a gain, they may be able to use either carryforward losses from previous tax years or intentionally realize losses in their investment accounts in the same tax year to offset the taxable gain from the sale of their investment property.

About Michael……...

Hi, I’m Michael Ruger. I’m the managing partner of Greenbush Financial Group and the creator of the nationally recognized Money Smart Board blog . I created the blog because there are a lot of events in life that require important financial decisions. The goal is to help our readers avoid big financial missteps, discover financial solutions that they were not aware of, and to optimize their financial future.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

What is tax-loss harvesting?

Tax-loss harvesting is a year-end tax strategy where investors sell investments that have declined in value to realize a loss that can be used to offset realized capital gains for the year. For example, if you realized a $100,000 gain from one stock, selling another stock with a $100,000 loss could eliminate the tax liability from that gain.

What is the difference between short-term and long-term capital gains and losses?

Short-term gains or losses come from investments held for one year or less and are taxed as ordinary income. Long-term gains or losses come from investments held for more than one year and qualify for lower, preferential long-term capital gains tax rates.

Can long-term losses offset short-term gains?

No. Realized long-term losses can only be used to offset realized long-term gains. However, realized short-term losses can be used to offset both short-term and long-term capital gains.

What happens if my realized losses are greater than my gains?

If your realized losses exceed your gains, the remaining amount becomes a loss carryforward. You can carry forward unused losses indefinitely and use them to offset future realized gains.

What is the $3,000 capital loss deduction?

Even if you have no capital gains, you can deduct up to $3,000 in realized capital losses per year against ordinary income. For married couples filing separately, the limit is $1,500. Any remaining unused losses can continue to carry forward to future tax years.

What are mutual fund capital gain distributions?

Mutual funds often distribute capital gains to shareholders at the end of the year, usually in November or December. These distributions create taxable income for the investor—even if no shares were sold. Tax-loss harvesting can help offset the tax impact of these mutual fund capital gains distributions.

What is the wash sale rule?

The IRS wash sale rule disallows a realized loss if you sell a security at a loss and buy a “substantially identical” security within 30 days before or after the sale. For instance, selling a Vanguard S&P 500 Index ETF and repurchasing a similar Fidelity S&P 500 ETF within 30 days would likely violate the wash sale rule.

Do loss harvesting rules apply to real estate and business sales?

Yes. The same loss-harvesting concept can apply when selling real estate or a business at a gain. Investors can use realized losses from their taxable brokerage accounts or carryforward losses from prior years to offset taxable gains from these sales.